Ocean scientists have, for the first time, successfully balanced the supply of food to midwater organisms with their demands for this food. The depth at which they consume sinking organic material regulates our climate by determining how much carbon is stored by the ocean and how much remains in the atmosphere.

The results of the study in the North Atlantic are published in the journal Nature. The research demonstrates how interactions between microscopic animals and bacteria in the ocean account for the consumption of sinking organic detritus called ‘marine snow’.

Lead author of the study, Dr Sarah Giering, now a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Aberdeen explained: “Microscopic plants in the upper ocean convert CO2 into organic matter. When these organisms die they sink into the deep ocean, carrying carbon with them. This fuels deep sea food webs and locks CO2 away from the atmosphere, helping to regulate the climate.”

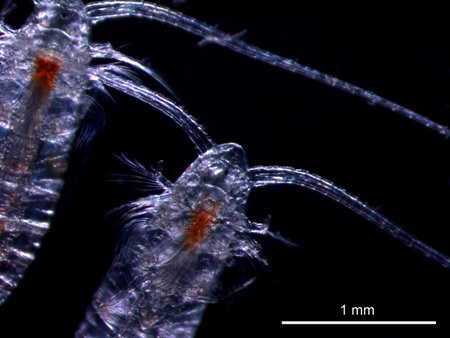

Organisms in the ‘twilight zone’, a layer of water between 50–1000 metres beneath the surface where light levels are extremely low, consume virtually all of the organic detritus, or ‘marine snow’ that rains down. Previous attempts to explain the loss of marine snow with biological activity in the twilight zone have failed, suggesting that the understanding of the processes within the ocean was incomplete.

“We show that a balance between food supply and demand is possible because of intricate linkages between zooplankton and microbes,” explained Dr Sarah Giering.

“When these microscopic animals eat marine snow, much of it is released as tiny suspended particles that are readily available to bacteria, which in turn convert it into biomass and CO2.”

Dr Daniel Mayor from the University of Aberdeen, a co-author of the research, said:

“The apparently wasteful process of zooplankton fragmenting, rather than ingesting, sinking detritus is central to understanding how the twilight zone works.”

CO2 released at depth can stay there for thousands of years, providing a natural mechanism for carbon storage.

Dr Giering said: “Marine organisms release massive quantities of CO2 in the deep ocean, keeping atmospheric CO2 concentrations much lower than if the oceans were devoid of life.

“Our findings are a major step forward, allowing us to explore the role of deep‐sea biota in regulating our climate.”

Dr Richard Sanders, Head of Ocean Biology and Ecosystems at the National Oceanography Centre and a co-author of the study added: “When predicting future atmospheric CO2 levels, it is important to understand how much marine snow is sinking to depth and where it is being consumed.”

The field studies took place in 2009 in the Porcupine Abyssal Plain in the North Atlantic.