A recent addition to the aquatic fauna of the Rhynie chert is a group of bizarre organisms which are termed euthycarcinoids. The euthycarcinoid body plan comprises a preabdomen with a variable number of segments or somites. On the ventral side these form distinct plates or sternites whereas on the dorsal side the plates (tergites) being fused appear larger and fewer in number so that two or sometimes three sternites appear to correspond with one tergite. Characteristically the appendages of the preabdomen are multi-segmented, almost antenna-like, with one leg pair per sternite. An apodous postabdomen with a variable number of segments ends in a pointed or styliform tail or telson. The systematic placement of euthycarcinoids remains somewhat problematic, since they show similarities with crustaceans and uniramian arthropods, including insects.

One species of euthycarcinoid has been found in the chert, Heterocrania rhyniensis (Hirst & Maulik 1926). It was originally assigned to the genus Crania after the collector and discoverer Rev. William Cran, but was subsequently changed to Heterocrania as the name Crania was preoccupied by a genus of brachiopod.

When first discovered, the affinity of Heterocrania was unknown, the fossil only being known from fragmentary remains lacking sufficient diagnostic features. It was only with the recent discovery of more complete specimens in the Windyfield chert that it became clear the animal was a euthycarcinoid (Anderson & Trewin 2003) (see inset below).

- Fossil Record

-

Euthycarcinoids are relatively rare as fossils. They are an extinct group of arthropods with a fossil record spanning from the Late Silurian to the Middle Triassic. The earliest euthycarcinoid fossil was described by McNamara and Trewin (1993) from the Tumblagooda Sandstone of Western Australia. The youngest fossil has been described from the Middle Triassic of Australia (Edgecombe & Morgan 1999). Upper Carboniferous euthycarcinoids have been recorded from Mazon Creek fauna (Schram & Rolfe 1982) and also in Europe (Anderson et al. 1997 , 1999 ; Secretan 1980 ; Wilson & Almond 2001). Heterocrania is the first euthycarcinoid known from Devonian rocks.

- Morphology

-

Heterocrania is a small euthycarcinoid, to date being the smallest of its kind described. In life it probably attained a length of approximately 15mm.

Head

Preabdomen

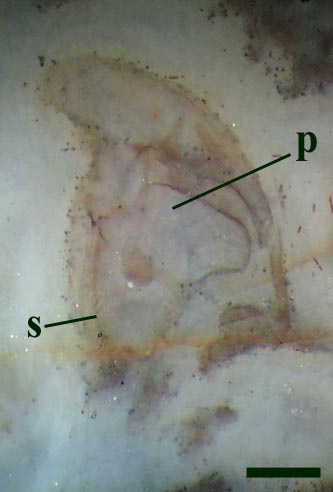

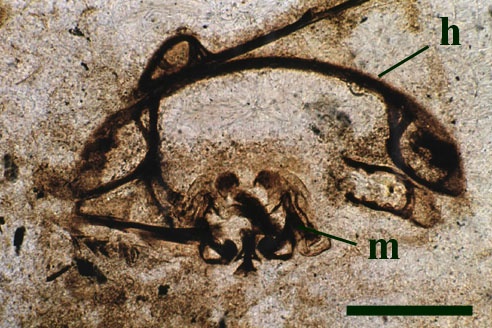

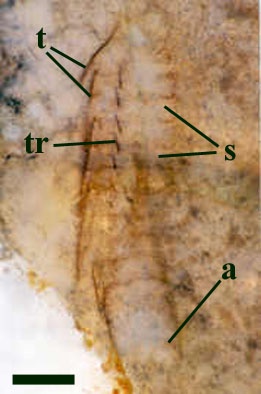

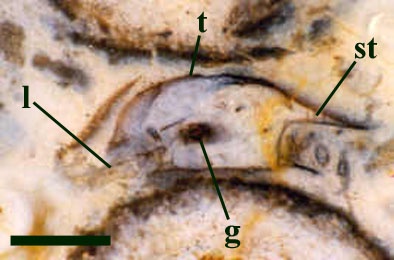

The tergites are convex and markedly wider than the flattened sternites, the lateral margins of the tergites forming shelf-like projections (Anderson & Trewin 2003). In transverse cross section, these lateral projections appear to be reinforced by cuticular struts separating the upper and lower surfaces of the tergite cuticle (see inset below). In some thin sections of the animal curious rod-like tubes are present internally, with a disposition of one pair per sternite (see inset right) and appear to correspond with the position of the bases of the leg appendages, for which they probably provided support.

In a few specimens an internal sub-cylindrical gut trace occurs, comprising amorphous organic detritus (see inset below).

Postabdomen and Tail

The postabdomen of Heterocrania comprises five apodous homologous segments. This arrangement suggests the euthycarcinoid belongs to the family Kottixerxidae. The tail or telson is of unknown length but appears to be similar in morphology to most other euthycarcinoids in being pointed and styliform.

Leg Appendages

- Palaeoecology

-

In the Rhynie chert Heterocrania is typically associated with the the crustacean Lepidocaris, the probable charophyte Palaeonitella, coprolites, algal and cyanobacterial filaments and often occurs in cherts displaying a clotted or 'mulm-like' texture. Heterocrania is therefore interpreted as an aquatic organism.

The morphology of the leg appendages suggests the animal was not suited to a predominantly swimming or nektonic lifestyle, as evidenced by the lack of paddle-like flattened podomeres and setae. Although Heterocrania may have been capable of limited swimming, it was probably more suited to burrowing or crawling on the substrate of freshwater ponds, feeding on organic detritus (Anderson & Trewin 2003).