This is a blog post reflecting on a recent research trip to South Africa. The role of the Schools of Law at the University of Aberdeen and the University of Stellenbosch together with the financial support of the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland played in making that trip possible is acknowledged and further explained below.

In blogging parlance, please note this is a “long read”.

Introduction – Scottish and Personal Perspectives on Land Reform

Towards the end of its first parliamentary term, the Scottish Parliament passed the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. This statute sought to broaden access to land in Scotland in two ways: in the sense of liberalising the law relating to outdoor access; and in the sense of giving some communities the right to acquire land in certain circumstances.

This legislation has been important for many people in Scotland. I suppose I am one of those people, but not in the sense that I have used it to acquire land or brought a test case to demarcate the limits of the right of responsible access. Instead, I find that I have written about it. A lot. This trend began when I was searching for an undergraduate LLB dissertation topic (in 2004). This post effortlessly evidences that the trend continues. I suspect I will write about it and the wider topic of land reform again. There are worse vices than writing about land law reform, I tell myself.

In writing that dissertation, it quickly became clear to me that land reform was not a peculiarly Scottish issue. Whilst it might be just about possible to offer an opinion on land matters in any given place by simply looking at that place, adopting such an approach restricts the scope of a study somewhat. Another thing that became clear was that it would be nigh on impossible to compare Scotland to every other legal system that also regulated land. This meant I had to whittle down my comparator jurisdictions a bit. Taking guidance from Scott Wortley (now at the University of Edinburgh, but then at the University of Strathclyde and also my dissertation adviser), South Africa was proposed as a prime candidate.

My dissertation ultimately became a critique of the new community rights to buy found in Parts 2 and 3 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. The dissertation looked both at the “blackletter” of the law and whether the 2003 Act could meet its stated policy goals. The research associated with the dissertation involved building on my existing knowledge of Scots land law and policy, whilst undertaking a desk-based and Scots law library-based study of South Africa.

With the online and library resources I had access to, I sought to gain any insight I could. (I found the book Land Title in South Africa , by Carey Miller with Pope (1999) particularly useful, then I was fortunate to work with Professor David Carey Miller in later years.) Several features of South African law were of particular relevance to my study. For example, I read of South Africa’s Communal Property Associations Act 28 of 1996, which gives communities a means to associate together to hold land. This was directly in point to my consideration of community rights of acquisition, allowing me to highlight the more flexible approach South Africa had for community bodies that could own land.

I also considered South Africa’s history, its new Constitution, and its programme of land restitution. These considerations were undeniably interesting, but not particularly useful to my immediate task. In fact, a chapter in a wide-ranging Scots/South African comparative study, it was noted by Professors Reid and van der Merwe that a comparison on these matters highlighted “difference and not similarity” (in Zimmerman, Visser and Reid (eds), Mixed Legal Systems in Comparative Perspective: Property and Obligations in Scotland and South Africa (2004) – more will be said about the similar legal systems below).

In relation to the specific researcg for my dissertation, much of my interest in wider South African land reform was necessarily put on the back-burner; something to come back to at a later stage. This research trip to South Africa gave me a chance to return to the issue, in the company of experts in South African law, with South African resources to hand, and indeed with a South African context to experience for myself. This post now offers some raw and eclectic thoughts about the trip. (I have also offered some thoughts on another aspect of my trip, where I had a cursory but instructive look at the Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic, which is available here.)

I should acknowledge that there are some things that this blog post will not cover. For example, this post will not seek to explain what makes for effective land reform. Nor will it directly set out how recent Scottish land reform laws are framed or operate: other resources are available for that (including on this blog). Attention is now firmly shifted to South Africa, but Scottish observations will be made where South Africa offers a suitable comparator. I should also declare that my observations on South African matters are offered with due deference to existing treatments of land reform by South African scholars (notably Pienaar, Land Reform (2014), and the already mentioned Carey Miller with Pope). Please also note that a complete analysis of the changing nature of land law since the end of apartheid will not be attempted here, to ensure this post remains (close to) a manageable length. This means the coverage will be selective at times, although further reading will be identified where appropriate. There are also some notable omissions from my South African coverage. For example, I say nothing here about national parks, although I can shield myself from accusations that I copped out of this topic by steering people to this post over at my personal blog. Another area not addressed is abandonment of land. This is not because the topic is uninteresting or uncontroversial: a forthcoming paper in the South African Law Journal by Richard Cramer, a PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town, will demonstrate that adeptly. It is also a topic that merits study from a Scottish perspective, and I am writing a paper of my own on it. That will follow in due course.

Enough scene-setting. Time for the meat of the post. (Which reminds me, one important lesson that I learnt on my trip is many South Africans like meat. The braais are amazing. Anyway, I digress…)

South Africa – constitutional land reform?

It is difficult to know where to begin in South Africa’s land reform story, but the 1990s offer a starting point with a certain logic. In 1994, the first multi-racial elections in South Africa brought Nelson Mandela’s political party (the ANC) to power and him to the office of President. This heralded a new political era and the end of the overtly racial system of apartheid that had influenced so much law and policy in that country, albeit that process was set in train by negotiations followed by an earlier interim constitution, then put firmly on a constitutional law footing when The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa came into effect on 4 February 1997.

Whilst aspects of the South African Constitution are unavoidably functional, other aspects are far from dry. The Preamble is simultaneously reflective, inspirational and pragmatic. Its words can be narrated in a compelling and captivating manner. (Incidentally, the American musician and spoken word performer Henry Rollins has done just that: I happened to attend one of his shows in Edinburgh when he diverted into a breathless, ranted appreciation of the Constitution. Footage of this from another show is available on YouTube.)

Chapter 1 then sets out the founding provisions, including section 1’s explanation of the basis on which the sovereign, democratic state is founded (including: human dignity; non-racialism and non-sexism; and supremacy of the constitution and the rule of law). Chapter 2 contains the Bill of Rights, which “affirms the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom” (section 7). Section 25 then provides constitutional protection for property. It is that “property clause” that is of most interest to land lawyers, and which kept coming up in my research about contemporary South African law. That is not to say other aspects of the constitution are not important more generally, or indeed specifically in the context of land. For example, a recent law on communal land ownership was struck down by the Constitutional Court because parliamentary process as mandated by the Constitution had not been properly followed. There are also provisions about cultural life and the environment that are important in the context of land. Section 26 on housing, and specifically the right not to be evicted without a court order (which will be returned to below) also merits attention. That notwithstanding, the property clause is the most sensible place to start any consideration.

Whilst the nine subsections of the property clause must be read together for a full picture, it is worth noting that it begins by providing that:

No one may be deprived of property except in terms of law of general application, and no law may permit arbitrary deprivation of property.

It then clarifies:

Property may be expropriated only in terms of law of general application: a. for a public purpose or in the public interest; and b. subject to compensation, the amount of which and the time and manner of payment of which have either been agreed to by those affected or decided or approved by a court.

Property clauses in other constitutions or similar rights documents (such as the European Convention on Human Rights) also make similar provision for the protection of property, but what is striking about the South African Constitution is it then goes on to say, “For the purposes of this section… the public interest includes the nation’s commitment to land reform, and to reforms to bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources.” This is a constitutional order that puts land reform in the foreground. (Those who wish read more should seek out A J van der Walt, Constitutional Property Law (3rd edition, 2011).)

For its Constitution alone, South Africa is worthy of study. This relatively young Constitution is already a crucial consideration in terms of who should control, manage and use land in that country. According to van der Merwe, Pienaar and Du Waal (writing in the Kluwer Law International publication South Africa which is part of Property and Trust Law in the International Encyclopaedia of Laws series, 2015), “The South African law of property has been the realm of South African law that has been most affected by the new South African Constitution.” Important as it is, the property clause of the Constitution did not sweep away the legal system that regulates the country’s land, nor did it instantly change who owned what at the time it came into force. This means an understanding of the manner in which the country developed, featuring waves of European migration following the establishment of a Dutch trading post at what is now Cape Town and subsequent incorporation into the British Empire, is important to understanding the legal migration of Roman-Dutch law that also occurred.

This also goes some way to explaining why a Scots lawyer does not feel wholly uncomfortable commentating on that legal development. This is not because Scots law migrated to the Cape. Rather, the Roman-Dutch law of the province of Holland went to the Cape, and then that law was flavoured by aspects of English law (English law being the system that followed the British Empire to its outposts). The mixture that emerged from this clash of legal traditions leaves an underlying property law system that is (or at least was) more familiar to continental European – or civilian – eyes than Anglo-American – or common law – eyes. Meanwhile, the Scottish system of land law draws heavily on Roman law, and whilst it too has been influenced by English law (owing to a shared legislature from 1707 and much in the way of shared experience and trade) its land law also remains somewhat civilian.

This coincidence might be useful for legal research purposes. However, as already noted, the new order that is emerging in South Africa – with its written Constitution featuring an explicit declaration that land reform is in the public interest, and recognition of customary or indigenous rights – demonstrates a trend that is not replicated in Scotland. It can also rightly be said that the conditions faced in South Africa, which exist because of a discriminatory framework, are unique (Pienaar, 2013). This lingers in a socio-economic situation that is very different to Scotland, a number of which I set out in this post about addressing access to justice via student law clinics (and specifically the Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic). As a result, comparisons are necessarily tentative and land reform solutions and mechanisms are not automatically transplantable. One comparison that can be made, however, is the simple fact that both jurisdictions have recently legislated for land reform. Some recent South African statutes will now be considered, alongside some new measures that have been proposed.

Legislation

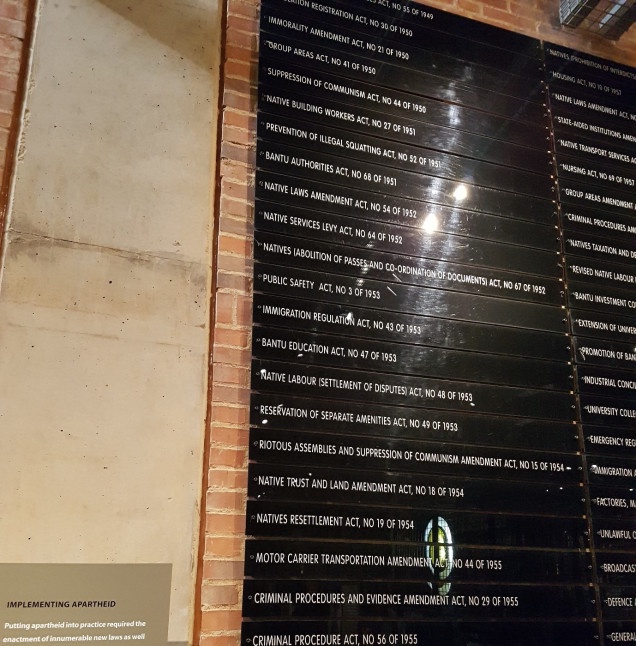

The legislative instruments that supported the apartheid regime are too numerous to mention here. For context, the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg displays a number of laws that were instrumental in that regime, as this amateur photo demonstrates (taken when I visited there).

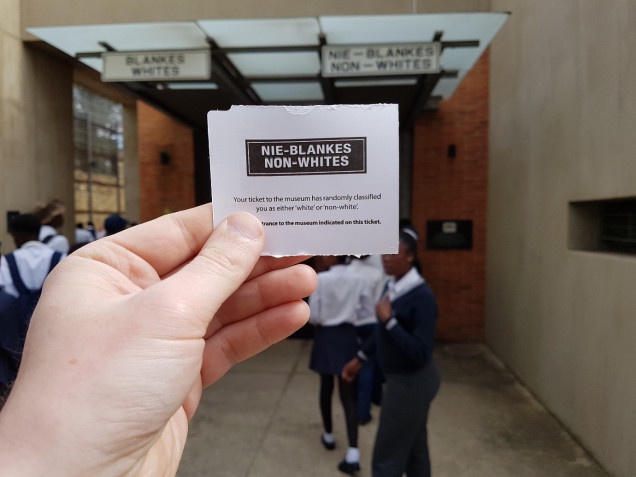

To digress for a moment, at the ticket desk for the museum each visitor was allocated a “white” or “non-white” ticket.

As you can see I was allocated a “non-white” ticket (which under the old rules could have meant I was one of many classifications, all ranking below white to a variety of degrees). This allocation meant I could only use one of the two entrances. As such I could not see the displays accessible via the other entrance (before all visitors were funnelled back together). I felt excluded. I guess that was the point…

Anyway, back to those statutes. Many of those related to land, in terms of regulating who was allowed to own land in certain areas, or indeed allowing people to be forcefully removed. Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom has numerous instances where such measures take centre stage, from the Group Areas Act 14 of 1950 and its successors (which Mandela notes that Daniel Malan described as “the very essence of apartheid”, and which features on the wall in the Apartheid Museum), to the clearing of Sophiatown (one of the oldest black settlements in Johannesburg). There were also older measures like the Natives (Urban Areas) Act 21 of 1923, which prohibited new freehold townships, and of course the Black Land Act 27 of 1913, of which Sol Plaatje famously noted that Africans awoke the morning after its passage to find themselves pariahs in the land of their birth. The importance of all these steps to the overall land question has been judicially recognised, in the case of Bakgatla-Ba-Kgafela Communal Property Association v Bakgatla-Ba-Kgafela Tribal Authority and Others [2015] ZACC 253. There, the South African Constitutional Court noted (at paragraph 2) ‘For decades restitution of land was the rallying point for the struggle against colonialism and apartheid. Regaining land ownership was the primary object of that struggle.’ (It then noted (at paragraph 3) that it was “not surprising that the Constitution guarantees land restitution and reform.” I will return to the Constitution in a moment.)

To paraphrase Carey Miller, such measures bolted onto the existing system of property law. That Roman-Dutch system was not in and of itself racist, but it was absolutist and put the holders of property rights in a strong (private law) position. If only certain people could access those rights in certain areas, only they could be in that strong position.

Fast forwarding to the modern era, racial statutes were repealed by the Abolition of Racially Based Land Measures Act 108 of 1991, but that step did not immediately undo the consequences of those measures. Meanwhile, even with their repeal it is not possible to ignore them. The consequences of some legal measures remain important, not only because they have influenced who might be owner now, but also because some of them (for example, the 1913 Act) are important in establishing who might have a claim to the restitution of land.

Back to the constitution, and related laws

The importance of the Constitution for land reform has been touched on already in this post. It mandates three broad ways in which land reform is to be achieved: restitution, redistribution, and tenure reform.

Restitution

Restitution will only be mentioned quickly here, not because it is not important, but (selfishly) because it is not important to the reform exercise that has taken place in Scotland. Some instructive observations can be made though.

By restitution, I mean “returning” property to someone (or someone’s descendants) where a previous act of expropriation that affected them can be traced. Whilst this may sound simple, there are a variety of factors to consider, not least the fact that the person who owns land in the present day may have had nothing to do with the original expropriation. There may also be issues of prioritising which wrong needs to be rectified: for example, Mandela himself notes the iMfecane (alternatively spelled as Mfecane or referred to as the Difaqane) left displaced people as refugees in the area where he grew up in the Transkei, even before you get to the upheavals caused by the British or the Voortrekkers. There may even be issues of competing claims.

Various jurisdictions have grappled with these issues and adopted a restitutionary approach to land reform, including in Eastern Europe and in other parts of Africa. Scotland has not adopted such an approach. South Africa has. It first did so via the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994, whereby claimants had to identify an act of dispossession that occurred after 19 June 1913 before restitution could take place. Any dispossessions from before that date leave those affected relying on other aspects of the wider reform program (discussed below). There was also a time-limited period in which claims could be made.

The merits of such cut-off dates can be debated. I will not do so here. I will however quickly note that there may be more restitution legislation in the pipeline, as a result of a decision of the Constitutional Court which declared that the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act 15 of 2014 was unconstitutional (owing to a lack of public participation in the law-making process). This legislation had sought to allow for new lodgements of land claims. The court gave the South African Parliament 24 months to rectify matters, meaning it has until July next year. It seems there will be new legislation. Like the earlier act that was ruled invalid by the Constitutional Court, this piece of legislation aims to provide a new five-year window for land claims to cater for those who missed a previous cut-off date in 1998. Depending on how this proceeds, this means the Land Claims Lodgement Centre might be busy again…

Thanks to Hansie and Melanie Geyser for pointing this sign out to me, then humouring me when I took a photo.

Another aside worth mentioning relates to something I spotted from the window of a bus tour, yet failed to photograph. This was a sign painted on a wall next to a crossroads in Soweto, urging people to lodge a land claim. Does Scotland need to do more to advertise its land reform laws? For my part, I think Scotland does okay, but I do appreciate I am a) interested in these things and b) on the internet too much. Maybe advertising on street corners in less salubrious post codes is something that could be considered in Scotland too.

Redistribution

Interesting as restitution may be, consideration of the redistribution aspect of land reform leads to a more instructive comparison between Scotland and South Africa. Here, the land that is subject to reform is being reallocated in a way that is not directly linked to a past wrong. Instead, present day land rights are being revisited to reflect present day needs. There is provision for this in the South African Constitution.

Scotland has a number of rights to buy land which facilitate land transfer from one party to another, including some situations where a tenant can buy out her landlord and also situations where a community can acquire land local to it from a private individual. This might be on a “first refusal” basis (i.e. a community will be given first dibs on any land a local landowner wishes to sell) or, in some circumstances, on a forced sale basis (i.e. the landowner has less of a say in when or indeed if the land is sold).

In terms of how much land is to be redistributed, the Scottish Government has indicated that it wishes to see 1 million of Scotland’s 20 million acres in community ownership by 2020. For its part, in 1994 South Africa announced a target of having 30% of agricultural land in black ownership by 1999. This target year was subsequently amended to 2014. Both targets have been missed. (Without commenting on whether either the 1 million acres or 30% target should be higher or lower, in can be noted that the scientific reasoning for either figure has not been made out, although the importance of having a target should not be dismissed.)

South Africa also has something of a community focus in this branch of the reform programme. The first statute that catches the eye is one I have already mentioned, namely the Communal Property Associations Act. It has been described (in the Bakgatla case) as “a visionary piece of legislation passed to restore the dignity of traditional communities. It also serves the purpose of transforming customary law practices.” It would be fair to say that the community associations that can be formed under that legislation have a bit more flexibility than the Scottish model. That said, Scotland has now increased versatility in this area, after the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 added the Scottish charitable incorporated organisation and the community benefit society as eligible community land holding bodies to what was previously the only option of a company limited by guarantee.

Another point that is worth noting here is – perhaps surprisingly – the legal rules in Scotland for redistribution of land seem a bit more radical. This is because South Africa (to date) has focussed on the willing buyer, willing seller model, whereas Scotland does allow for some compulsion in limited circumstances (in relation to crofting land, and there will soon be other rights in relation to neglected, abandoned or environmentally mismanaged land). That is only part of the story though. The overall South African position as regards communal land is slightly difficult to comment on in a blog format such as this, but suffice it to say it is complicated by a history of racial land policy that went as far as setting up puppet black states called “Bantustans”. There are then a variety of modern factors such as the Communal Land Rights Act 11 of 2004 and multifarious questions about what or who embodies a community. (That 2004 statute, like the more recent restitution statute already mentioned, was also struck down by the Constitutional Court, again for improper parliamentary process.) There is also a possible reassertion of tribal landownership. This is difficult to comment on from a Scottish perspective, but it seems almost akin to Scotland trying to reintroduce the heritable clan jurisdictions that were abolished in the tumultuous times of the 1700s (albeit without such a time gap).

In terms of future redistribution, ongoing concerns about the pace of land reform has led to much speculation about what should happen next and in particular whether and if so when South Africa will move away from its willing buyer, willing seller model. (There are also questions about expropriation and compensation.) Much of this might be tied to the new Regulation of Agricultural Land Holdings Bill (http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/40697_gen229.pdf) and a new Land Commission. That’s right, South Africa could be getting a Land Commission, not long after Scotland introduced one via the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016. It appears the South African version will be a little bit different to the Scots version though: for example, it will seek information about landowners (such as race, gender and nationality) and check on the use and size of the agricultural land holding. In due course it will have a role in relation to the proposed capping of the size of agricultural holdings (see below) and redistribution of land from holdings that are above the cap.

From discussions with postgraduate students at Stellenbosch, I know there are some questions about how such a new Land Commission will interact with the existing Deeds Registry (where title deeds relating to ownership are registered), so this is something to keep an eye on. There is also an ongoing issue in South Africa in terms of simply working out who owns what. To an extent, this chimes with current Scottish developments, where there is a drive to complete a transition of all titles to the Land Register by 2024, but more importantly there is a related drive to work out who holds controlling interests in any landowning entity (from Part 3 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016). Both jurisdictions could benefit from comparisons with the other.

As for the Regulation of Agricultural Land Holdings Bill itself, that could cap the size of South African landholdings or prohibit the acquisition of ownership of agricultural land by foreigners. Similar proposals were explored by the Scottish Land Reform Review Group, although a) it did not go so far as to propose what the cap might be, and b) the foreign ownership restriction would have targeted ownership of land by non-EU entities, rather than all foreigners. Neither of these proposals were included in the most recent Land Reform Act, but if South Africa takes steps in this direction that will be yet another reason that makes South African land reform something to watch. (As an aside, it can be noted that one reason for the non-EU entity point not being included in recent Scottish reforms is up in the air following the Brexit vote. There were fears such a step might breach EU law. Depending on the exact flavour of Brexit, this obstacle might be removed.)

Tenure reform

Tenure reform amends the manner in which control is exercised over property. This branch of South African land reform has been especially important, in relation to security of tenure, i.e. a right to stay on land. This is normally important for the likes of labour tenants on farms (and specific legislation was passed for that). There have also been two important statutes that apply to regulate eviction depending on where an occupier of land is.

In urban areas, there is a chance to grab a slice of the PIE. (Sorry, that is terrible legal pun.) The Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act 18 of 1998 both prohibits unlawful evictions and provides procedures for the eviction of unlawful occupiers. This legislation is analysed in a chapter by Professor Anne Pope in Professor David Carey Miller’s forthcoming festschrift, which will be published by Aberdeen University Press, so I will not say too much about it here. All I will note is it essentially provides that evictions can only take place when it is just and equitable for that to happen, and this might mean a landowner will not be able to recover possession from an occupier in all circumstances.

In rural areas, in addition to protections for labour tenants, protection is afforded by the Extension of Security of Tenure Act 62 of 1997. This conferred security of tenure on those who had, at one stage, been occupying land with the consent of the owner, and again this prevents eviction from a home unless it is just and equitable. An additional point worth noting here is that eviction actions can take place in a Magistrates’ Court (roughly equivalent to a Sheriff Court), but eviction orders are subject to automatic reviews by the dedicated Land Claims Court. All of this means people do not lose their homes lightly.

At this point I offer one aside from a Scottish perspective. In 2003, legislation was passed by the Scottish Parliament with a view to giving an element of security of tenure to a certain class of rural occupier, where that occupier (and active farmer) held land via a juristic personality called a limited partnership, with the landowner being a partner in that venture. The limited partnership was either of a definite length or the landowner was able to bring it to an end by taking certain procedural steps. The reform enacted by the Scottish Parliament was rather technical, to say the least: sections 72 and 73 of the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 are not easy to understand, but essentially they sought to upgrade the active farmer into a class of tenant that enjoyed greater security of tenure. Technical issues aside, the more fundamental problem is that a court ruled this reform was a breach of an affected landowner’s human rights, as the imposition of a secure tenancy was found to be an interference with the landowner’s peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. Remedial legislation followed. (Further reading is available on my personal blog.) The analogy between the jurisdictions and the situations is not exact, and, for Scotland, any moment to cater for these individuals has passed. That notwithstanding, the South African model of extending security of tenure seems much simpler than the route which was eventually followed by the Scottish Parliament. As such, any future attempts by Holyrood to confer security of tenure to any class of occupiers might benefit from a comparative approach.

Another aspect of South African law, or perhaps even South African culture or philosophy, is the notion of ubuntu, which flows from ideas of human interdependence and dignity. Whilst there is no single definition of ubuntu, this did not stop it playing a role in the case of Port Elizabeth Municipality v Various Occupiers 2005 (1) SA 217 (CC). As noted by Justice JY Mokgoro in a short chapter in Frank Diedrich (ed), Ubuntu, Good Faith and Equity: Flexible Legal Principles in Developing a Contemporary Jurisprudence (Juta, 2011), “ubuntu was the underlying principle for the Court’s articulation of the proper procedure that must be followed when evicting vulnerable people from their homes.” Now, I am not going to be so crass or naïve as to suggest ubuntu‘s balance of individual rights and a communitarian philosophy could simply be lifted across to Scotland, but it did make me ponder a couple of things. In relation to historic Scotland, it reminded me of the Highland notion of duthchas, implying a connection to land that transcends legal ownership, which the historian Professor Jim Hunter and others have written about. More importantly, in relation to modern Scotland, I wondered if the was an analogy with the new land rights and responsibilities statement, which is provided for by Part 1 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016. Whilst landowners have always had certain obligations and responsibilities in Scots law, it is genuinely an exciting time for Scottish land law as Scottish society tries to pin down what a landowner’s responsibilities should be. Whether it is from ubuntu or from something else entirely, South Africa could be able to teach us something.

Conclusion

For the purposes of a provocative conclusion, let me replace that optimism with a dose of cynicism. Comparisons are tricky. One problem with comparisons is knowing where to stop. Given I have cleared 5,000 words, now seems as good a time as any. Before I go, I will set out some words of caution about comparative law, then draw some final conclusions.

The trouble with analogies is that they are different. So it goes with comparative law. I touched on some of the different socio-economic factors in my earlier post about the Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic. In addition to setting out some of those issues, that post explains how places like Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic try to address the unmet legal need of indigent South Africans, and of course there are fundamental matters like access to justice at play when it comes to the land question. This can be seen from the case of Nkuzi Association v The Republic of South Africa (LCC/10/01), where legal representation of respondents in eviction matters in terms of the Extension of Security of Tenure Act became compulsory. Scotland and South Africa do have some key historical and contemporary differences, which means there are certain limitations when it comes to transplanting ideas or rules from one legal system to another.

That said, I hope you learnt something from this blog post. I found it challenging to write, in part because I was an outsider looking at South Africa, but mainly because I wanted to do it justice. In fact, I spent more time writing this post than I had initially planned to. I do not regret that though. I felt it was important to write up my trip in the fullest possible way and this post, coupled with my note about the Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic and even my post about national parks, just about does that.

To reflect on the trip as a whole, I feel I learnt a lot. In addition to having access to the legal materials to allow me to draw this post and my wider thoughts together, I also benefited immensely from chatting to students, scholars and many other people I met along the way. For example, in a seminar at Stellenbosch I was asked to what extent the Scottish land reform programme was about human dignity (because the South African programme is), which really got me thinking. Then there were discussions with students and postgraduates at Stellenbosch and the University of Cape Town, which kept me on my toes as I tried to answer questions like the deceptively simple, “Why is Scotland doing what it is doing?” or the grenade of “Wait, what is crofting?” Then there were chats with non-lawyers, who politely/incredulously asked what I was doing in South Africa. I hope I managed to answer them at the time, and I hope this blog post serves as an answer to anyone who was too shy to ask that question directly.

This is a blog post by Malcolm Combe