Authors

Download

content

“Children in families with strong community ties are surrounded by developmental influences” (Elder & Conger, 2000, p.125). This insight emphasises the importance of a child’s community in their global development. As an Early Years practitioner, at a primary school in a town in the North East of Scotland, I regularly encounter various aspects of the community and often reflect on how much of an influence they have had upon the children within my classroom. The key theme of this Feature Article is to explore what ‘community’ is in relation to a child and explore how the influences of a community can affect a child’s learning and development. This will be done by evaluating a wider definition of ‘community’, using models such as Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Framework (1979) and indicators proposed by the Scottish Government, which I will outline below.

The notion of ‘community’ is varied with several views stating different criteria as to which parameters are necessary to constitute one, suggesting that it cannot be defined outright (Bruhn, 2011; Hardcastle, Powers et al, 2011; Rosenblatt, 2015). Bryk and Driscoll (1988) define a community as the attendance and communication of a collective set of values and common agenda with a shared ethical conduct. The ‘Combat Poverty Agency’ (2000) shares a similar understanding, suggesting that ‘community’ is a collective and communicative group of individuals who share a common interest. This links with the importance of communication within a community suggesting that relationships matter greatly and that social networks are invaluable in the development of communities (Field, 2003). The idea of ‘community’ can also relate to a geographical area and common goals within that area (Alperson, 2002; Cordner, 2008). Together, these definitions align with my experiences and what is found in the school community I work at. The community is engaged in activities and events (such as school fundraisers; open days for parents and councillors; community sport clubs) to involve everybody and work together to support all within the local area, including those whom are in areas of deprivation.

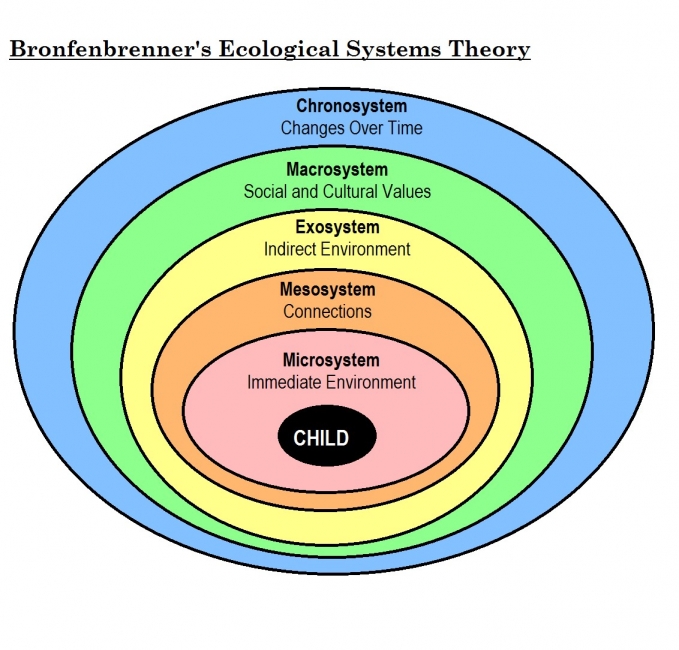

In order to aid my understanding of the complexity of the notion of ‘community’ and the community that I work within, I engaged with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological System (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This framework helps provide a structure to the factors in a community which may affect the children in my class and their development. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Framework is a series of environmental and personal contexts which can affect the development of a child (Munhall & Fitzsimons, 2001; Spencer, Harpalani et al, 2006) (See Diagram 1). These contexts are referred to as the: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

The influence of these ‘systems’ on children can be seen fluidly by different people and professionals throughout the surrounding community (Underdown, 2007).

Diagram 1: ‘Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological System’, Psychology Notes HQ (2013)

The microsystemrefers to the child’s ‘immediate environment’, which can include the child’s: close family, neighbourhood or school contexts (Berk, 2000). The microsystem has the biggest influence on child development and can create experiences which can be extremely beneficially nurturing, or detrimental to their development (Rogoff, 2003). This primary influence stems from the child developing love and trust for significant family members whom can help to create or damage a healthy mentality (Pipher, 1996; Swick, 2004). Within my school community, it is clear that the microsystem has an impact on children’s behaviour and academic achievements.

The mesosystem connects various close influences from the Microsystem together and provides the connections to the different parts of the child’s life such as when teachers communicate with parents or a social worker communicating with a sibling of the child (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Berk, 2000; Kawk and Jain, 2016). The exosystem portrays a larger social system wherein the child doesn’t function directly. The influence from this system occurs through the interaction with other structures (Berk, 2000), such as parent work schedules or the pressures of family life (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Galinsky, 1999).

The macrosystempertains more to the cultural and indirect influences affecting a child and their development. This refers to the influence of organisations related to the child, including: religious groups, ethnicity or social class (Berk, 2000; McLaren and Hawe, 2005). Shelton and Brownhill (2008) suggest that a child who has been exposed to and influenced by a religion from a young age may have differing behaviours and attitudes towards school due to the cultural norms instilled upon them. Finally, the chronosystemrefers to the influence of time and how it relates to the child’s environment. These can be exterior influences, such as: the death of a close family member or internal influences such as puberty (Bronfenbrenner, 1989; Shaffer and Kipp, 2010). Additional influences, for example, divorce can greatly influence how a child develops, depending on how the divorce unfolds and at what stage it happens in a child’s life (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992, cited in Shaffer and Kipp, 2010).

Within Scotland, the external influences which affect a child’s learning and development have been recognised by government policy and legislation, leading to the creation of a relevant and supportive framework. The Scottish Government developed the framework known as ‘GIRFEC’: “Getting It Right For Every Child” (Scottish Executive, 2007), to support children by supporting the variety of professionals who can influence to the development of a child’s life (Florian, Black-Hawkins et al, 2007; Hannah, Ingram et al, 2014). This policy, created by the Scottish Government, has therefore been developed to focus on an Early Years intervention and prevention strategy, as opposed to waiting until the family are in difficulties (Scottish Executive, 2007). Additionally, it strives to ensure that the ‘rights of the child’ and their wellbeing are at the core of all services, with the aim of ensuring that the correct service is available to the child or young person at all times (Rose, 2012; Coles, Cheyne et al, 2016).

Within the framework are a set of indicators: Safe; Healthy; Achieving; Nurtured; Active; Responsible; Respected; Included; which is often abbreviated to SHANARRI. These help to specify areas for professionals to look at in supporting a child (Scottish Executive, 2014) and their global development. Tisdall and Davis (2015, p.217) state that a child’s quality of well-being is “defined” by the SHANARRI indicators, suggesting that we can determine a child’s level of well-being by using this as a guide. Tisdall and Davis (2015) further debate however that these indicators may state what well-being is made up of, but do not clarify what it is on a wider scale. This is due to its failure to look at other contributing factors to well-being such as societal status, allocation of resources and access to legal support. This suggests that while it may support us as Early Years Practitioners in understanding the well-being of the children in our class, it does not clarify the deeper aspects of a child’s well-being and how it may be affected by the macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), for example.

The community surrounding a school can have varied effects on the social, emotional, mental development and learning of children within it (Hamilton, 2004; Schaps, Battistich et al, 2004; McMurray and Clendon, 2011) which is very apparent in the school I work in. Many of the children that I teach come from a deprived area, which can have a negative effect on their health, learning and attitudes towards school (Ashford and LeCroy, 2009). The area produces statistics of deprivation in areas such as income, health, crime and housing, with the most recent census highlighting a high percentage of adults without qualifications, high unemployment and for whom English is an additional language, suggesting that this is a difficult area for children and families to develop in (Local Authority Statistics).

Despite this, the area of deprivation that I work in has a very positive outlook with various groups and societies which link and support each other within the community, such as extra-curricular clubs through the school or sports clubs through community centre or local football team. Linked to this, there is much encouragement in the community to succeed academically with families interacting with the school and other support agencies to seek help in ensuring that their children’s needs are met. This suggests that we are beginning to move away from the “Cultural Deficit Model” (Song & Pyon, 2008, p. 216) and are no longer attaching stereotyped expectations to a child because of their local area.Pence (1988, cited in Howard and Johnson, 2000), states that a strong social community can operate as a safety hub for children, providing support agencies and networks.

The supportive networks found throughout my area help children to succeed in a variety of ways, as they are a part of something (Thomson, 2010). The School I work at is the central part of a community as it provides a geographical area of focus and allows people from all cultures to interact with each other (Vestermark, 1996; Horn, 2002; Malik, 2013). As well as the formal education provided, the school and the local football club provides the community with the facilities for children to develop various skills in extracurricular activities (Schneider, 2014; Joslyn, 2016), of which there are many within the area. Children often perceive school as a safe place to be compared (Ezati, Ssempala et al, 2011; Salter, 2012; Roffey and O’Reirdan, 2013). Having these services available allows children to have a supported network in their lives from which they can develop the various skills they need to succeed, irrespective of the prejudice of their area.

The community is vital to the children living in the area as it provides them with the support they need to feel safe; the activities and services they need to stay healthy and active and the encouragement which they need to achieve their goals. The professionals and networks that are available can care for them in, what is not often perceived as a caring environment. The groups, activities and school allow children to feel respected, let them practise responsibility and feel included. Despite the area being high in deprivation, I conclude that a strong community which works together for the benefit of each other can help to nurture and protect the well-being of the children in the community and support the wider education and development of Scotland’s youth.

References

ALPERSON, P., (2002). Introduction: Diversity and Community. In: P. ALPERSON, ed. Diversity and Community: An Interdisciplinary Reader. Oxford: Blackwells, pp. 1-30.

ASHFORD, J. B. and LeCROY, C. W., (2009). Human Behavior in the Social Environment: A Multidimensional Perspective. 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

BERK, L., (2000). Child Development. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

BRONFENBRENNER, U., (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

BRONFENBRENNER, U., (1989). Ecological Systems Theory. In R. Vasta, ed. Annals of Child Development, Volume 6, Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp.187-249.

BRONFENBRENNER, U., (1994). Ecological Models of Human Development. International Encyclopedia of Education, Volume 3, 2nd edition. Oxford: Elsevier pp. 37-43.

BRUHN, J. G., (2011). The Sociology of Community Connections. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

BRYK, A. S. and DRISCOLL, M. E., (1988). The High School as Community: Contextual Influences and Consequences for Students and Teachers. Available: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED302539.pdf [Date Accessed: 20th October 2016].

COLES, E., CHEYNE, H., RANKIN, J. and DANIEL, B., (2016). Getting It Right for Every Child: A National Policy Framework to Promote Children's Well-Being in Scotland, United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly: A Multidisciplinary Journal Of Population Health and Health Policy, 94(2), pp. 334-365.

COMBAT POVERTY AGENCY, (2000). The Role of Community Development in Tackling Poverty. Dublin: Combat Poverty Agency.

CORDNER, A. E., (2008). An exploratory study of one charter school director as a community builder within the school. PhD Dissertation. University of Hartfor Deparment of Educational Leadership. Available: http://search.proquest.com/docview/304375032?fromunauthdoc=true [Date Accessed: 20th October 2016].

ELDER, G. H. and CONGER, R. D., (2000). Children of the Land: Adversity and Success in Rural America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press Ltd.

EZATI, B. A., SSEMPALA, C. and SSENKUSU, P., (2011). Teachers Perceptions of the Effects of Young People's War Experiences on Teaching and Learning in Northern UGANDA. In: J. PAULSON, ed. Education, Conflict and Development. Oxford: Symposium Books Ltd, pp. 185-208.

FIELD, J., (2003). Social Capital. London: Routledge.

FLORIAN, L., BLACK-HAWKINS, K. and ROUSE, M., (2007). Achievement and Inclusion in Schools. 1st ed. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

GALINSKY, E., (1999). Ask the children. New York, NY: William Morrow & Company.

HAMILTON, R., (2004). School, Teachers and the Education of Refugee Children. In: R. HAMILTON and D. MOORE, eds. Educational Interventions for Refugee Children: Theoretical Perspectives and Implementing Best Practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer, pp. 83-96.

HANNAH, E. F. S., INGRAM, R., KERR, C. and KELLY, T. B., (2014). Inquiry-Based Learning for Interprofessional Education. In: P. Blessinger and J. M. Carfora, eds. Inquiry-Based Learning for the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences: A Conceptual and Practical Resource for Educators. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 105-206.

HARDCASTLE, D. A., POWERS, P. R. and WENOCUR, S., (2011). Community Practice: Theories and Skills for Social Workers. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HORN, R. A. J., (2002). Understanding Educational Reform: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc.

HOWARD, S. and JOHNSON, B., (2000). What makes the difference? Children and teachers talk about resilient outcomes for students at risk. Educational Studies, 26(3), pp. 321-327.

JOSLYN, E., (2016). Resilience in Childhood: Perspectives, Promise & Practice. London: Palgrave.

KWAK, D.-H. and JAIN, H., (2016). The Role of Web and E-Commerce in Poverty Reduction: A Framework Based on Ecological Systems Theory. In: V. SUGUMARAN, V. YOON and M. J. SHAW, eds. E-Life: Web-Enabled Convergence of Commerce, Work, and Social Life: 15th Workshop on e-Business, WEB 2015, Fort Worth, Texas, USA, December 12, 2015, Revised Selected Papers. Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland, pp. 143-154.

MALIK, A., (2013). Citizenship education, race and community cohesion. In: J. ARTHUR and H. CREMIN, eds. Debates in Citizenship Education. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 67-82.

McLAREN, L. and HAWE, P., (2005). Ecological Perspectives in Health Research. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(6), pp. 6-14.

McMURRAY, A. and CLENDON, J., (2011). Community Health and Wellness: Primary Health Care in Practice. 4th ed. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier Australia.

MUNHALL, P. L. and FITZSIMONS, V. M., (2001). The Emergence of Family Into the 21st Century. London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers International.

PIPHER, M., (1996). The Shelter of Each Other: Rebuilding Our Families. New York, NY: Ballentine Books.

PSYCHOLOGY NOTES HQ, (2013). What is Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory?.

Available at: https://www.psychologynoteshq.com/bronfenbrenner-ecological-theory/ [Date Accessed: 20th October 2016]

ROGOFF, B., (2003). The Cultural Nature of Child Development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

ROSENBLATT, F. F., (2015). The Role of Community in Restorative Justice. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

ROSE, W., (2012). Incorporating safeguarding and well-being in universal services: developments in early years multi-agency practice in Scotland. In: L. MILLER and D. HEVEY, eds. Policy Issues in the Early Years. London: Sage, pp. 153-196.

SALTER, A., (2012). Family Stew: Our Relationship Legacy. Bloomington, Universe.

SCHAPS, E., BATTISTICH, V. and SOLOMON, D., 2004. Community in School as Key to Student Growth: Findings from the Child Development Project. In: J. E. ZINS, ed. Building Academic Success on Social and Emotional Learning: What Does the Research Say?. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, pp. 189-212.

SCHNEIDER, B. H., (2014). Child Psychopathology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE, (2007). Getting it right for every child. Available: http://www.gov.scot/resource/doc/1141/0065063.pdf [Accessed 15th October 2016].

SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE, (2014). Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014, Edinburgh: Scottish Executive. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2014/8/pdfs/asp_20140008_en.pdf [Date Accessed: 15th October 2016]

SHAFFER, D.and KIPP, K., (2010). Developmental Psychology: Childhood and Adolescents. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

SHELTON, F. and BROWNHILL, S., (2008). Effective Behaviour Management in the Primary Classroom. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

SONG, S. Y. and PYON, S. M., (2008). Cultural Deficit Model. In: N. J. Salkind and K. Rasmussen, eds. Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology, London: Sage, pp. 216-217.

SPENCER, M. B. et al., (2006). Understanding Vulnerability and Resilience from a Normative Developmental Perspective: Implications for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Youth. In: D. J. Cohen and D. Cicchetti, eds. Developmental Psychopathology, Volume 1 Theory and Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, pp. 627-673.

SWICK, K., (2004). Empowering Parents, families, schools and communities during the early childhood years. Champaign, IL: Stipes.

THOMSON, J. K., (2010). Learning Together with Children. 2nd ed. Bloomington Universe.

TISDALL, E. K. M. and DAVIS, J. M., (2015). Children's Rights and Well-Being: Tensions within the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. In: A. B. Smith, ed. Enhancing Children's Rights: Connecting Research, Policy and Practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 214-227.

UNDERDOWN, A., (2007). Young Children's Health and Well-Being. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

VESTERMARK, S. D. J., (1996). Critical Decisions, Critical Elements in an Effective School Security Program. In: A. M. Hoffman, ed. Schools, Violence, and Society. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, pp. 101-122.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.26203/2kx6-0847Published in Volume 24 Issue 2 Research & Children in the North,