A Tribute by Clive M. Rice, Emeritus, Department of Geology and Geophysics

Peter Evans Brown was born and raised in Kendal in the Lake District, a place he loved and returned to regularly throughout his life.

There he developed a keen interest in rock climbing that served him well in his future career. These visits often from far afield were facilitated by his penchant for fast cars and powerful motorbikes. He joined the Fell and Rock Climbing Club in 1948 and attended the annual Dinner for many years. A strong rock climber, he once led a climb up Hells Groove on the East Buttress of Scafell for the club.

He attended Manchester University and graduated in 1952 with First class Honours in Natural Sciences. A PhD followed in 1955 based partly on samples collected from the Skaergaard intrusion as a member of the 1st British East Greenland Expedition in 1953, led by the distinguished geologists L.R. Wager and W.A. Deer.

The Skaergaard layered basic intrusion is considered to be one of the most famous and scientifically influential of all igneous intrusions and this experience inspired much of his future research. While at Manchester he met his wife Thelma (deceased) and they had two sons Ian and Andrew. He is survived by Andrew. Not only was Peter a talented rock climber but he also represented the university at cricket as a formidable left arm fast bowler.

After University came three years with the Geological Survey in Tanganyika, as it then was, employed as a geologist/mineralogist involved in field work and mapping. Adjusting to the different scale of mapping compared to the UK was challenging and, although puzzled initially by all the annotations on the field maps, he quickly appreciated one of them MMBA (Miles and Miles of B------ Africa!). Camping involved listening to unfamiliar wildlife noises at night and unknown creatures sliding down the outside of the tent and 'somewhat interrupting sleep'.

In 1959 he was appointed to a lectureship in the Department of Geology at Sheffield. During his time there he supported some key staff appointments and had a major impact on research in geochemistry and mineralogy and also teaching, especially the practicals. He established a geochemical laboratory and adopted the United States Geological Survey "rapid" methods of silicate analysis. Peter was prone to spoonerisms and is remembered for addressing a group of first year students, including the author, in the Lake District 'Here I am standing on an erratic block'. The reader can work that one out.

A further expedition to East Greenland led by W.A. Deer followed in 1966 and in 1971 Peter led a Sheffield expedition to the same area, which included Jack Soper, a colleague, lifelong friend, and climbing buddy. A small wooden sealing boat was chartered in Norway and they sailed through rough seas and pack ice to their destination, arguably a metaphor foretelling his later career in senior management! The Greenland terrane is inhospitable, mountainous and divided by glaciers strewn with crevasses and Peter`s leadership, climbing and geological skills were invaluable in these and later expeditions.

Peter was appointed to a Chair of Geology at Aberdeen University in 1973 and, following retirement of the incumbent two years later, he became Head of Department and Kilgour Professor and later served as Dean of Science. He was an important modernising influence at Aberdeen and, as at Sheffield, introduced a strong multidisciplinary research ethic by staff appointments. In due course these enabled advantage to be taken of the great opportunities offered by North Sea oil. He was also a respected Chair of the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Grants Committee.

He contributed to other aspects of department life for example the annual staff- student cricket matches, where his bowling was often decisive. Opening the batting on one occasion he was bowled first ball, much to his astonishment and everyone's amusement, by a female student who unbeknown to Peter was a fine player. For his leadership at Aberdeen and his wider contribution to Geology he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1978

The period of expansion and success for Aberdeen was brought to a sudden halt by the University Grants Commission (UGC) Earth Science Review in 1988. It was a debacle for small geology departments in general and staff reductions in Aberdeen resulted in Peter transferring to St Andrews. There he was inducted as Professor of Geology in July 1990, a chair that he held until his retirement in 1995, thereafter continuing as Emeritus Professor.

At that time the geology course at St Andrews had a marked bias towards petrology and his arrival was much welcomed. He was a master of the petrological microscope and enthusiastically shared these skills with students in practical classes. Out of the classroom his climbing skills were again valuable while supervising research in challenging locations including Ben Nevis.

Peter returned to Greenland on four further expeditions, including as leader in 1974. In 1980 he was invited to join the Grønlands Geologiske Undersøgelse Peary Land–Kronprins Christian Land Expedition to the far north of Greenland. Supported by helicopter, it mapped the Kap Washington volcanic sequence on Gertrude Rask Land in latitude 83°30'N, the most northerly land in the world and the ultimate wilderness where a fellow member and Aberdeen colleague Ian Parsons observed: 'The whole of humanity is beneath ones feet'.

Peter's enduring research interest was in structural, petrologic and geochemical studies, especially of the Caledonian igneous and metamorphic rocks of Scotland and the Tertiary granites, layered basic intrusions and volcanic rocks of east Greenland and their links to the opening of the north Atlantic. In the 1960s Peter recognised that the new techniques of radiometric dating would be fundamental to understanding magmatic events and the terranes which host them. Working with colleagues over that decade he published a series of papers on the radiometric ages of the granites, basic rocks and metamorphic rocks of northern Britain.

When it became clear that ages determined in the laboratory were not always compatible with field interpretations Peter applied his keen understanding of field relations and the influences of metamorphism and structural events to explain some of these differences. His research paved the way to a reassessment of magmatism in the Scottish Highlands constrained by radiometric dating. His 1991 review "Caledonian and Earlier Magmatism" in the 3rd edition of the Geology of Scotland was an important synthesis, which formed the basis of many future studies and applications of new methodologies.

Cricket provides a metaphor for an important part of Peter's character. He played with a straight bat and people knew where they stood. Allied with his calm, non-confrontational style and a clear idea of the objective made Peter a highly respected administrator at university and national levels.

He was able to resolve a controversial issue between the two UK Royal Societies. In the mid 1980s, the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) planned to celebrate the bicentenary of James Hutton's insights on the nature of granite magmas with a major international conference. Separately, the Royal Society (of London) had been planning its own symposium on the origin of granites for around the same time in 1987. This unfortunate clash was resolved by Peter as Chair of the RSE Organising Committee by skilfully negotiating a combined conference, the first scientific meeting jointly hosted by these august societies in over two centuries of co-existence.

Furthermore he succeeded in locating the joint conference at the RSE in Edinburgh and its success led directly to quadrennial meetings of the Hutton Origin of Granites conference and well regarded thematic volumes of proceedings. Each of the major continents has hosted at least one of these events.

Another of Peter’s unsung contributions was his vision and unwavering support for isotope geochemistry in Scotland following the 1967 establishment of the Isotope Geology Unit at the Scottish Universities Research and Reactor Centre (SURRC) at East Kilbride. His support, particularly during various financial crises, ensured that Scotland punched well above its weight in the geosciences for decades.

Peter's scientific collaboration with SURRC initiated sulphur stable isotope research at the Centre and led several years later to the important NERC contract to operate the Isotope Geosciences Support Facility. An important petrogenetic study of Proterozoic rapakivi granites in south Greenland found an unexpected high level of oxygen isotope homogeneity over a wide geographical area. Alkali feldspar δ18O averaged 10.2 ± 0.4‰ and there was no distinction between the black and white facies of feldspar. This suggested intensive mixing and homogenisation between a mantle-derived and a sediment-influenced Archaean crustal contribution to the initial magma, the melt of which was relatively anhydrous.

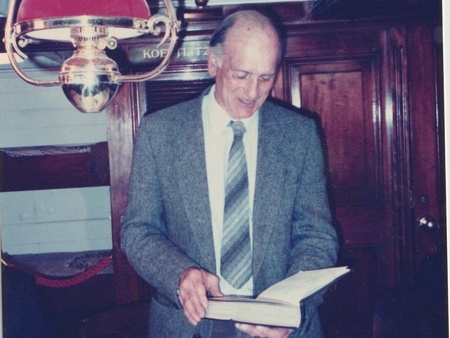

On Peter's retirement in 1995 his St Andrews colleagues organised a dinner attended by close geological associates from all regions of the UK to honour and pay tribute to his achievements. As befitting his polar achievements (and ignoring the issue of hemisphere) the event was held on RRS Discovery, the expedition ship supporting the exploration of the Antarctic by Scott and Shackleton. Peter was tricked into going to Dundee and while taking a brief look at the famous ship after dark was surprised by the party awaiting him.

After retirement Peter greatly enjoyed his field visits to the Highlands with old friends and colleagues including Jack Soper, Ian Dalziel and Tony Harris, where they delved into some of the old chestnuts of Scottish geology. Indeed Peter continued until quite recently to ponder how the various episodes of granite magmatism might fit current tectonic models for the geological evolution of the Highlands.

I am indebted to all the friends and colleagues who have enriched this tribute with their memories. Two summaries of Peter as a man make a fitting conclusion.

The photograph from the wardroom of RRS Discovery shows Peter examining with pleasure a surprise gift of a book and captures the thoughtfulness, reserve and dignity which accompanied all his actions. Tony Fallick (SUERC).

Peter was a modest man who never sought credit for important achievements. He will be remembered by all who knew him as a valued colleague, an outstanding petrologist and a good friend. He made a difference in difficult times. Ed Stephens (St Andrews University).