What finding seaweed at new depths in Antarctica means in the context of climate change

Professor Frithjof Kuepper has spent his career carrying out seaweed research in some of the world’s most uninhabited and undiscovered places. His work has seen him gather an immense knowledge of life under water as well as many valuable samples. The photos he shares here are mostly from a trip to Antarctica with some from the Canadian Arctic. And he believes his research could help us to answer some of the biggest questions challenging the sustainability of our world.

It’s considered the earth’s most hostile environment.

A place where temperatures can plunge as low as -90C and where very few humans live permanently.

Yet it’s a land of stunning natural beauty, home to a plethora of incredible wildlife and a habitat which may hold the answers to some of the greatest challenges the world faces today.

Antarctica, a world only a few will be lucky enough to experience.

Algae specialist

For Professor Frithjof Kuepper, Chair in Marine Biodiversity at the University of Aberdeen, the world’s second-largest continent houses a magnitude of fascinating science.

He has spent his career travelling the world exploring deep waters, often diving himself and gaining a unique insight into the ecology of seabed communities. An expert in seaweed biodiversity and biochemistry, Professor Kuepper joined the University from the Scottish Association of Marine Science in Oban. He has previously carried out research diving expeditions in the Arctic, Falkland Islands, Ascension, Chile, the Mediterranean, the Gulf, California / USA, Malaysia as well as Antarctica.

He spent six weeks in the icy land of Antarctica over the mid-summer months of December and January with the goal of exploring what the vast icy waters of the Southern Ocean can offer the modern world.

But even in summer the conditions in Antarctica are extreme, and the utmost caution must be taken with all activities.

His trip certainly wasn’t without its trials, indeed even getting into the water to start exploration was a challenge.

Staffing is limited, most people working there have at least one job and divers’ access to the water can be cancelled at a moment’s notice if the huge leopard seals are spotted.

Deepest seaweed

But when Professor Kuepper did manage to investigate these freezing waters, he discovered a type of seaweed growing at depths not previously known. The project is also exploring how seaweeds have grown in areas that were covered by Antarctic glaciers for thousands of years and how they can thrive while spending half the year in darkness under the cover of icebergs.

Working at Rothera Research Station on Adelaide Island off the southwestern Antarctic Peninsula and by using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from a small boat, Professor Kuepper and his team of researchers meticulously explored the icy waters.

Seaweeds are a hugely important natural resource which provides a home to marine organisms like barnacles, snails, sea urchins, crabs and mussels.

They are also a natural carbon sink and may be able to help protect the environment in the future.

In Antarctica, scraping of the seabed by icebergs can remove seaweeds from shallower areas which can lead to loose material being found at depths where it is not growing.

Previous deeper collections (below conventional SCUBA diving depths) have relied on dredge/grab samples or drop camera surveys but these remote techniques cannot conclusively prove that the algae are living as they may have detached through ice scouring.

Due to the cold temperatures the seaweed takes a long time to decompose so it can be confused as growing in the deep waters. The ROV helped the team to test and collect the seaweed but Professor Kuepper also carried out research by diving.

The researchers found the seaweed, the red alga Palmaria decipiens, at 100 m below the surface and collected samples for further examination. DNA sequencing was then used to confirm the type of seaweed.

Professor Kuepper added: “Our research aimed to clarify the maximum depths that seaweeds grow at in Antarctica and we used the ROV to look for seaweeds attached to hard substrate, in order to avoid mistaking them for algae which could have drifted down from shallower waters.

“The ROV allowed individual specimens to be inspected closely and from multiple angles, unlike methods such as video sledges or drop cameras.

“We now know that seaweeds can live at least down to 100m depth in Antarctica. That is quite a lot, but we can’t rule out that they may live even deeper.

Huge potential

Professor Kuepper believes his findings move science that bit further forward.

He explains: “Seaweeds have the potential to play a huge role in protecting the environment by storing carbon at the bottom of oceans when they die. Seaweeds are also an important food source to numerous animals and fish and have been eaten by people in many coastal communities in parts of the world for centuries.

“Seaweeds have been used in a variety of cosmetic and pharmaceutical goods and, being a renewable resource, they represent sustainable products.

“Finding Palmaria decipiens at 100 m depth is important for furthering our knowledge of Antarctica, a continent that is so important to understand for addressing the environmental challenges the world faces today.”

Funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and published in the journal Polar Biology, Professor Kuepper’s research involved a collaboration between the University of Aberdeen, the University of Southampton, the British Antarctic Survey and the University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece.

Investigating how the deep-water seaweeds can survive in the dark for many months when there is very little sunlight and thick ice is blocking what there is, may lead to discovering different ways in which we can protect our environment.

“The findings from this research bring us to a better understanding of how ongoing climate change is changing marine biodiversity in areas of shrinking ice shelves of the polar regions – and of the unique adaptations that polar marine life has not just to cope with freezing temperatures, but also prolonged periods of darkness.”

Pylaiella

Pylaiella

Climate change emergency

The urgency of the climate change crisis is keenly felt in Antarctica. Professor Kuepper witnessed the Sheldon Glacier from a distance of around 3 km from the edge. Just in the 1990s the shrinking glacier extended to the point on the water where he took the picture. The recession of this glacier is considered by BAS scientists as a strong example of climate change in the area of Rothera.

Dreamland

But what is life really like as a research scientist in Antarctica?

Professor Kuepper concludes: “Life in Antarctica is very good indeed - in a way, it feels like being in a better society. It struck me that hardly anybody talks about money and politics. Indeed, money and politics are almost irrelevant. Also, I noticed that people hardly ever argue. Instead, they talk of the rest of civilization as "the real world", as if being in Antarctica is indeed a life in Utopia, or a dream that will at some point abruptly come to an end.”

Professor Kuepper’s blog can be viewed here.

Photos:

1. Iceberg at Rothera taken from the shore.

2. Frithjof Kuepper by Charlie Bibby (Financial Times)

3. The research icebreaker of the British Antarctic Survey, RRS James Clark Ross, re-supplying Rothera Research Station

4. Expedition to Anchorage Island for collecting snow algae together with Dr. Matt Davey (Univ. Cambridge, now at SAMS, Oban)

5. Juvenile elephant seals playfully fighting in shallow water

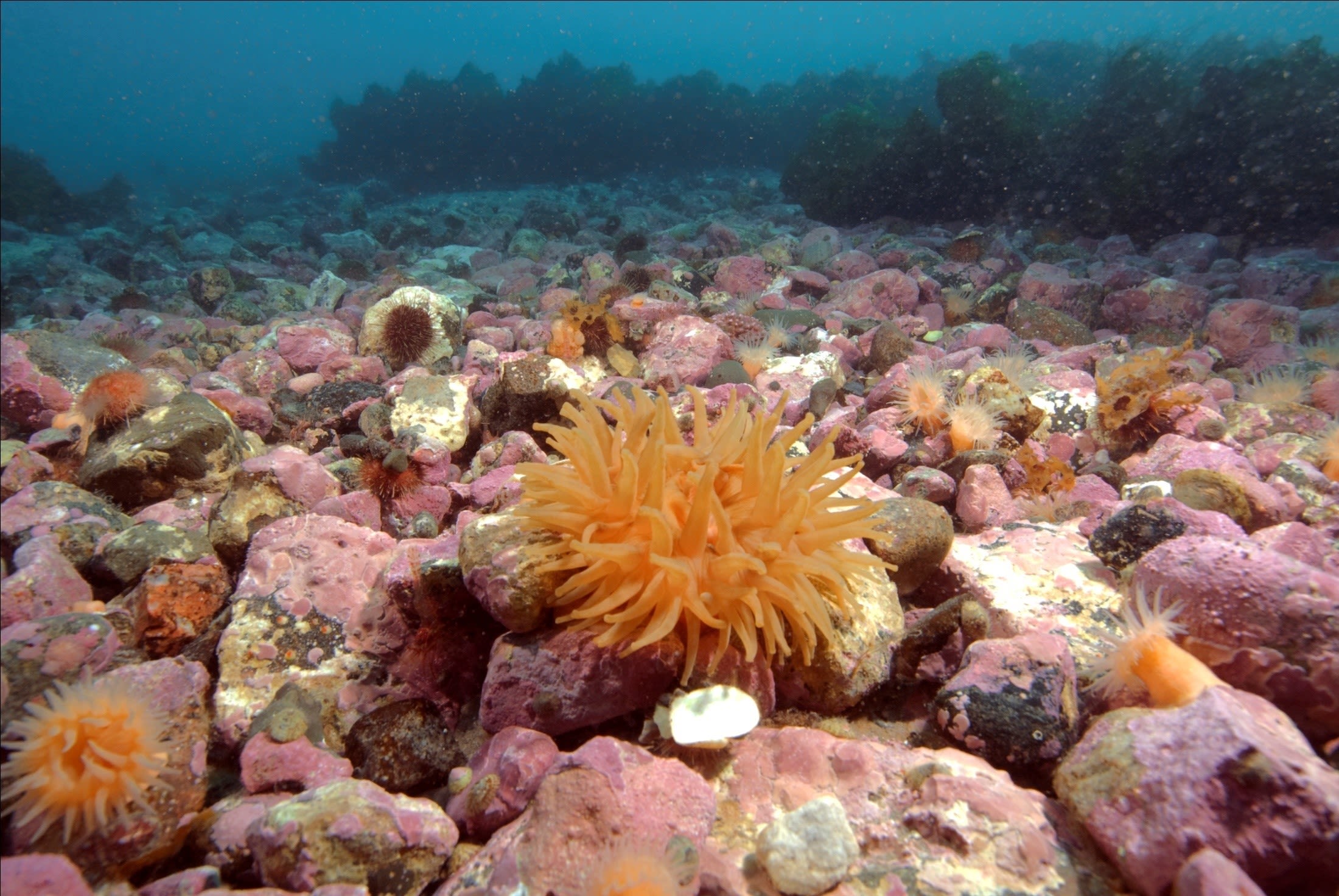

6. Coralline red algae (the pink crusts covering rocks) and sea anemones off the coast of northern Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic (photo by Martin D.J. Sayer, UK National Facility for Scientific Diving)

7. The brown seaweeds Fucus evanescens and Pylaiella off the coast of northern Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic (photo by Martin D.J. Sayer, UK National Facility for Scientific Diving)

8. Frithjof Kuepper diving in the Canadian Arctic, summer 2009 (photo by Martin D.J. Sayer, UK National Facility for Scientific Diving)

9. Frithjof Kuepper in Antarctica (photo by Charlie Bibby, The Financial Times)

10. The brown seaweed Pylaiella off the coast of northern Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic (photo by Martin D.J. Sayer, UK National Facility for Scientific Diving)

11. Penguin on iceberg near Rothera Research Station

12. “Supermoon” (the moon being exceptionally close to the Earth) over the Arrowsmith Peninsula of the Antarctic mainland

13. Adelie penguins, Minke whale and Skua near Rothera Research Station