Nathaniel King

The University of Aberdeen’s first African-born black student and a pioneering practitioner of medicine

As the University of Aberdeen celebrates its Winter 2020 graduates, Dr Richard Anderson, Lecturer in the History of Slavery, explores the life of Nathaniel King, the University’s second black student and the first born in Sub-Saharan Africa [1] .

Nathaniel, whose parents were liberated slaves, gained a medical degree in 1874. He took the skills gained in Aberdeen back to Nigeria where he pioneered Western medicine and campaigned for improvements to sanitation and education for local people.

He became well-known for his willingness to treat African patients who could not afford to pay his fees.

Such was his reputation that following his death at the young age of 36, during a smallpox epidemic in Lagos, a fund was raised to create a memorial stained-glass window in a chancel of Christ Church in the Faji district of Lagos, dedicated to his life and achievements.

Nathaniel was born in Hastings, Sierra Leone, on 14 July 1847.[2] His parents, Thomas and Mary King, were from Yoruba-speaking Egba regions of present-day Nigeria, until they were enslaved during a period of civil wars in the Yoruba kingdoms in the first decades of the nineteenth century.

Sold to European slave traders on the coast, Nathaniel’s parents were intercepted at sea by British naval forces and legally emancipated in Sierra Leone’s capital of Freetown. They became two of many ‘Liberated Africans’ who were settled in Hastings, one of the villages British officials established on the outskirts of Freetown in the 1810s.

Nathaniel’s father Thomas was educated in the colonial schools of the Church of England’s Church Missionary Society (CMS). He converted to Christianity and became a catechist and “native pastor.”

In 1841-42 Thomas participated in the Niger Expedition, an ill-fated British missionary expedition to Lokoja at the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers in present-day Nigeria.

After his return to Sierra Leone, he and Mary had two sons, Gabriel and Nathaniel. Despite the failure of the Niger Expedition, in 1849, he returned to proselytize among his fellow Yoruba speakers, accompanied this time by his wife, Gabriel and the now two-year-old Nathaniel. The fledgling CMS Yoruba Mission was based at Abeokuta, an Egba settlement established in c.1830 by refugees of the Yoruba wars.

Henry Venn

Henry Venn

Early life

The young Nathaniel attended the CMS Theological Institute at Abeokuta, where he came to the attention of the CMS missionary doctor and Cambridge graduate A.A. Harrison. Henry Venn, the honorary secretary of the CMS, had appointed Harrison to establish a medical school – the mission’s first in West Africa - at Abeokuta.

Harrison selected Nathaniel and three other promising students from the Theological Training Institution.

The boy spent his mornings at the Institution followed by afternoons in which Harrison taught a range of topics from anatomy and physiology to botany, zoology, chemistry, and mathematics. Nathaniel became Harrison’s personal assistant, until the doctor died in 1865.

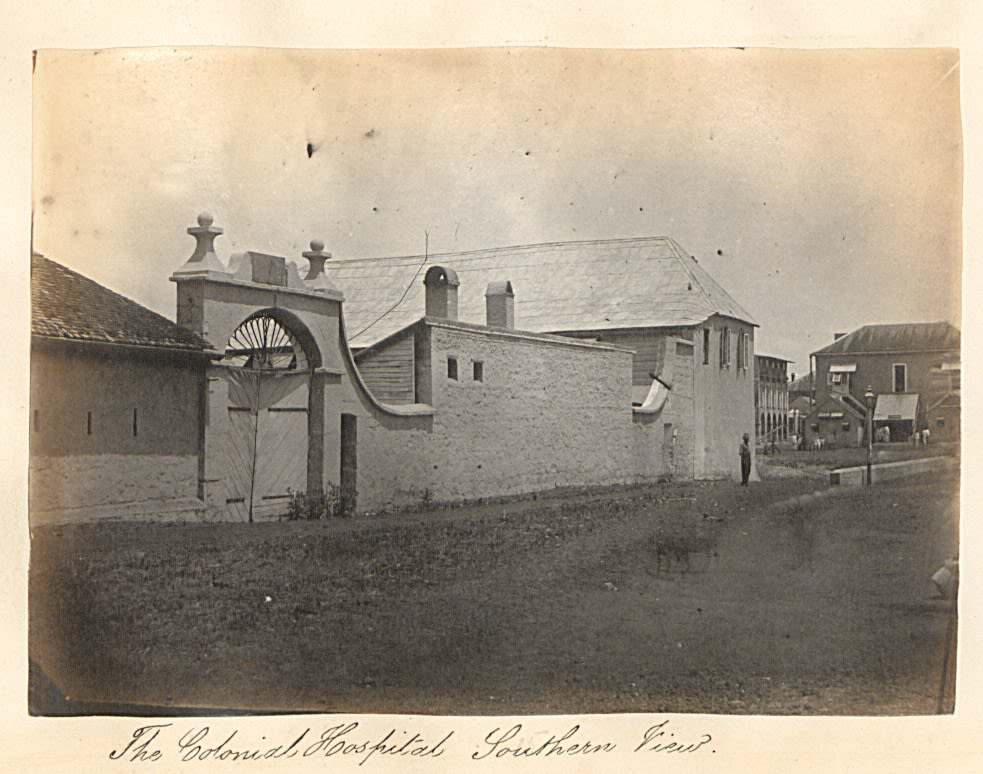

Venn asked that King be sent back to Sierra Leone in 1865 at the age of eighteen, where King studied at the CMS Grammar School and worked for two years as a dispenser. Here King served as an apprentice to Dr Bradshaw of the colonial hospital.

The colonial hospital complex was previously the Liberated African yard where tens of thousands of enslaved Africans, including both of Nathaniel’s parents, would have first landed in Sierra Leone.

University years

In 1871 King left Sierra Leone for England. He first completed clinical studies at King’s College, London and qualified as M.R.C.S. in 1874.

Nathaniel then proceeded to Aberdeen. Though King was the first black African-born student at Aberdeen, he was one of an increasing number of colony-born British subjects who travelled to Britain for education.

By mid-century, the offspring of educated and affluent Liberated Africans – increasingly referred to as the creole or Krio elite – were travelling to Britain to study medicine and law.

Nathaniel may have chosen Aberdeen on the advice of Samuel Rowe, an Aberdeen medical graduate and colonial official who served for twenty-six years in West Africa.

Rowe graduated at Aberdeen in 1865 in medicine and surgery and held several posts including colonial surgeon at Cape Coast and Lagos.

Nathaniel King graduated M.B. and C.M. in 1876. The latter degree entitled him to M.D. three years subsequently.

The University of Aberdeen Roll of Graduates incorrectly lists his place of birth as Lagos, though it was here that Nathaniel would work for the remainder of his life.

Samuel Rowe

Samuel Rowe

Missionary Meeting at the Wilberforce Oak, June 21, 1873. There are several known versions of this image. The image pictured here is courtesy of Between the Covers-Rare Books, Inc., New Jersey, where this copy was for sale in 2020.

Missionary Meeting at the Wilberforce Oak, June 21, 1873. There are several known versions of this image. The image pictured here is courtesy of Between the Covers-Rare Books, Inc., New Jersey, where this copy was for sale in 2020.

A medical pioneer

Nathaniel returned to Lagos after his graduation. By 1876, fifteen years of British colonial occupation had reduced the former independent kingdom to a colony, and brought the thriving European trade in slaves to an end.

King worked as the medical attendant to the agents of the Church Missionary Society at Lagos and occasionally acted as locum at the Colonial Hospital.

Many European residents in Lagos preferred King’s professional services over those of the Colonial Surgeon. He became well-known for his willingness to treat African patients who could not afford to pay his fees.

The Eagle and Lagos Critic, an early African-owned newspaper, praised “his boundless charity, unostentatiously rendered to many in this land.”

Outside of his work, Nathaniel was a prominent member of the educated Lagosian elite. The Lagos Observer praised how “Socially, ‘Marble Hall’ [the location of his offices on Broad Street] was only open to all who sought him for advice and help” and that “His house was virtually a literary club.”

Nathaniel was also a Senior Deacon of a Masonic Lodge. He presided over the public examination of students at the CMS Grammar School.

He joined with other prominent Lagos residents in petitioning the British government for improved public drainage and sanitation; assistance to vernacular schools; and representation within the Legislative Council. He also served on the Editorial Board of the Lagos Observer, one of the first African-owned newspapers in the colony.

Nathaniel Kind died at the young age of thirty-six on 12 June 1884, during a smallpox epidemic in Lagos. Charting his life after Aberdeen, his obituary in the Lagos Observer recalled how Nathaniel:

returned to Lagos in the year 1876, and from that time, his life was one course of usefulness. Dr. King gradually gained the confidence of the community, till his name became a household word. As a medical man, the poor and rich were at all times accessible to him. Poverty never influenced him in his zeal for the sick. “To save life is the medical man’s first consideration, and his remuneration the second,” was a favourite expression of his, and this spirit actuated him throughout all his noble career.

After his death, compatriots created the King’s Memorial Fund. The notion of memorialising a prominent member of society such as Nathaniel King via a physical memorial was something of a novelty at this time.

Raising funds via subscription, the committee dedicated a memorial stained-glass window in a chancel of Christ Church in the Faji district of Lagos.

A brass plaque below the window noted Nathaniel King’s educational accomplishments as the University of Aberdeen’s first African-born black student and a pioneering practitioner of Western medicine in colonial West Africa.

[1] The author wishes to thank Kristin Mann and Lisa Lindsay for their assistance.

[2] Some historical sources incorrectly list his place of birth as either Lagos or Abeokuta in present-day Nigeria.