Saving the secrets of one of history’s darkest chapters

“One of the most remarkable collections anywhere in the world that chronicles war, revolution, and conflict in the 20th century.”

When University of Aberdeen historian Professor Thomas Weber first met Gerd Heidemann, the former investigative reporter was living in a small apartment surrounded by boxes of files.

Heidemann’s once stellar career, which saw him win the World Press Photo Award in 1965, had been reduced to tatters when his so called ‘scoop of the century’ turned out to be the mistake of a lifetime.

His name had become synonymous with a 1983 news story in which he announced to the world he had uncovered Hitler’s lost diaries – only for them to be unmasked as elaborate forgeries and for Heidemann to serve time in prison for his role in the scandal, which he denied to his dying day.

But Professor Weber was interested not in that story, comprehensively covered on front pages around the world, but in the little-known archive of materials Heidemann had spent a lifetime acquiring and which remained an almost untapped resource for historians.

From his modest Hamburg home, Heidemann had amassed thousands of folders of documents, photographs and hundreds of hours of recordings from key figures of the Third Reich – even renting a basement in which to keep them.

In his quest to learn more about the archive, Professor Weber uncovered a much more complex life story for Heidemann. Frequently dismissed as a Nazi sympathiser, just a few days before his death, in an interview with Professor Weber, he was ready to speak publicly about how he had in fact spent many years assisting the Israeli foreign intelligence agency, Mossad, in efforts to hunt down notorious Nazis including Josef Mengele, infamous for his medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz.

Professor Weber brokered exchanges between Heidemann and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in the USA, where Weber is a Visiting Fellow, to ensure this vital repository of previously unseen material can be preserved in their specialist archives.

We explore the remarkable story of how these files made their way from a basement in Germany to an elite US university where significant sections have now been digitised and released to the world to help unlock the remaining secrets of Nazi Germany and conflict in the 20th century.

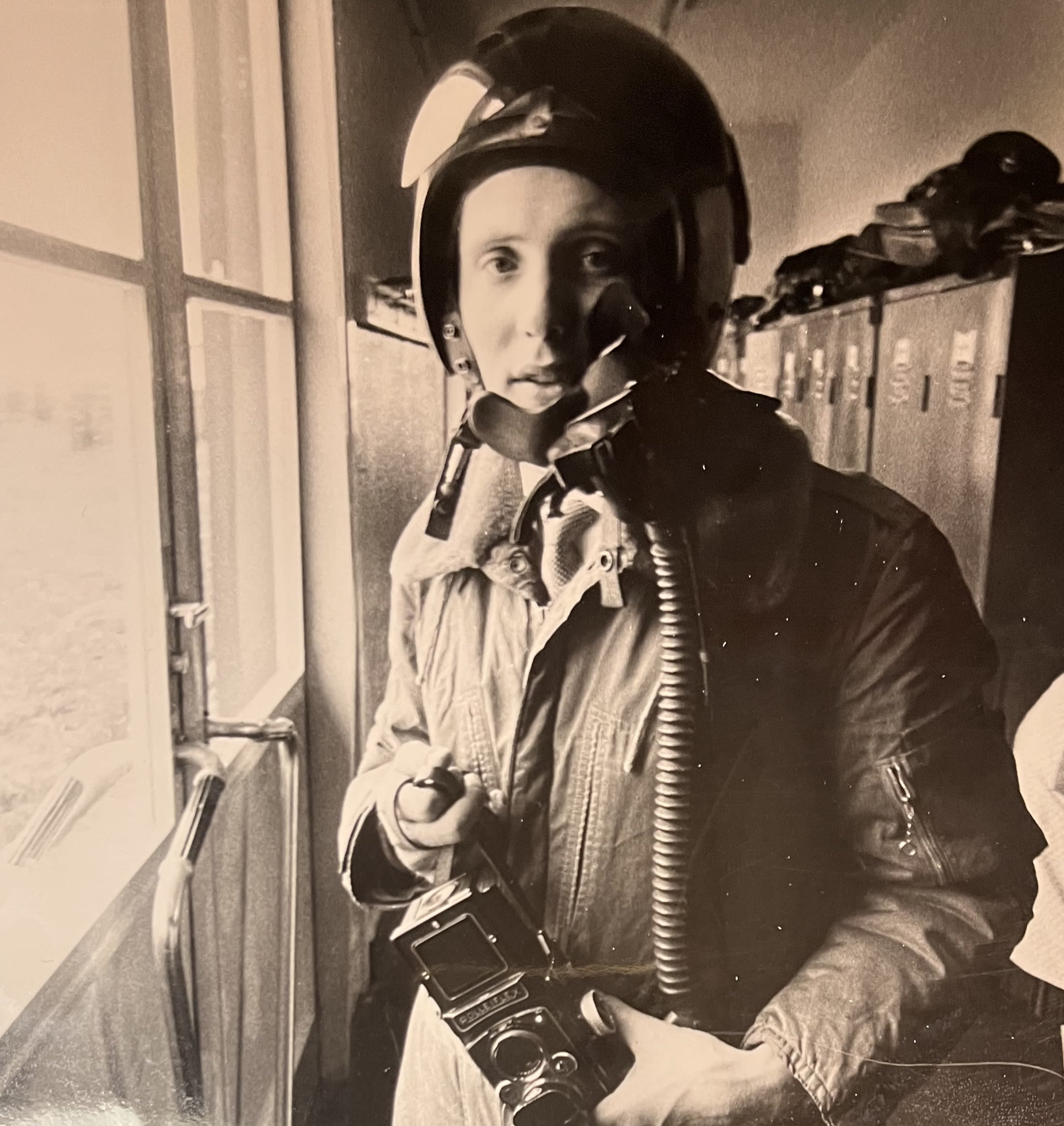

A young Gerd Heidemann

A young Gerd Heidemann

A friend of the Nazis or a ‘bloodhound’ determined to expose the truth and bring Nazi war criminals to justice?

When Gerd Heidemann died in 2024 aged 93 obituaries varied in their assessments of his life. Many noted that his editors at the respected German magazine Stern called him ‘the bloodhound’ because of his intrepid nature. Others applauded his long stints covering post-colonial conflicts in Africa and the Middle East.

All referred to his 1983 entanglement with the Hitler diaries and subsequent downfall and there was tacit agreement that descriptions of his later years were best limited to a few short sentences.

The New York Times reported that he ‘hoarded uniforms, medals and other trinkets; palled around with former Nazi generals’. But Professor Weber says this misunderstands the nature of the collections he compiled and the complex relationship Heidemann had with the Third Reich.

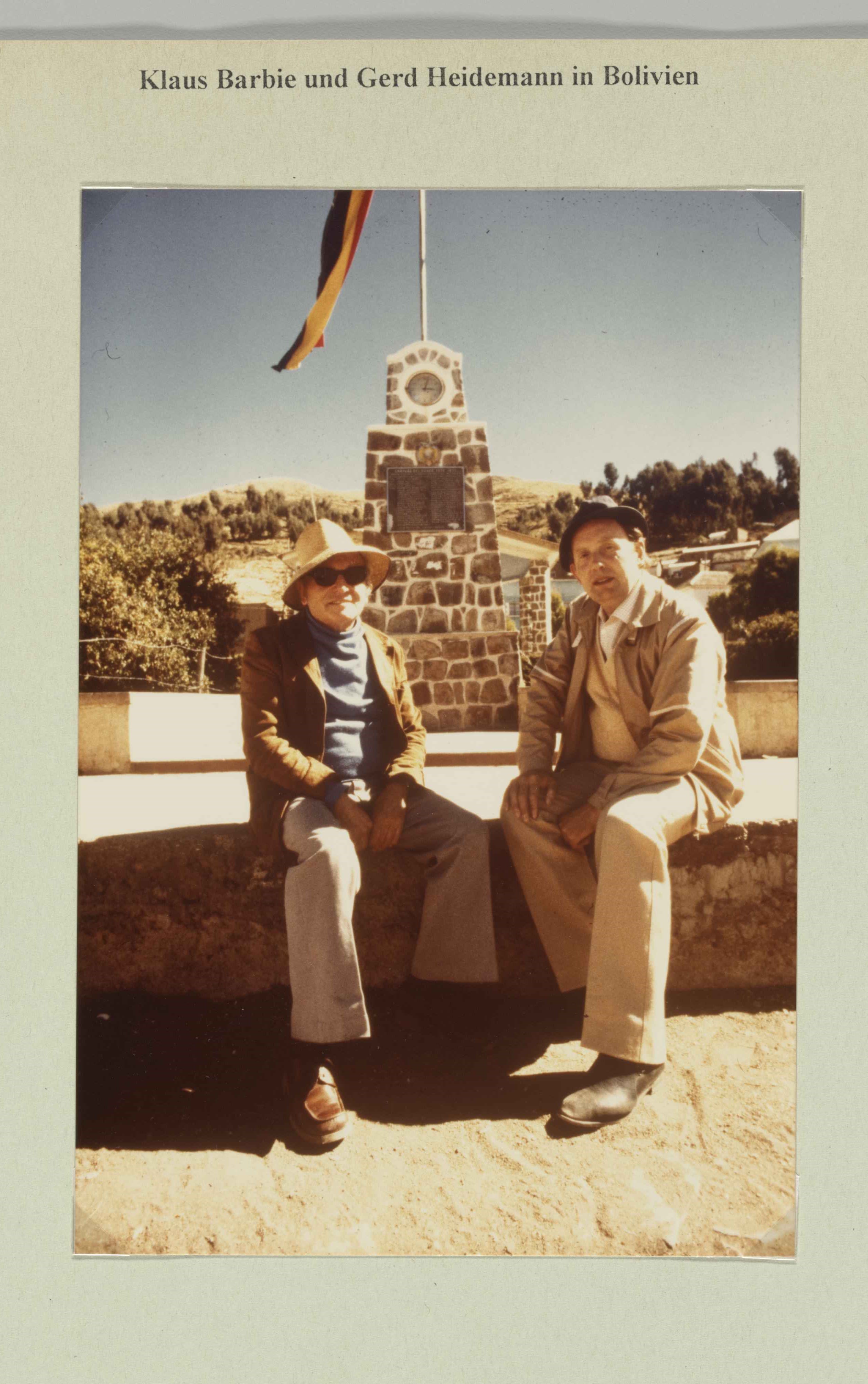

It was Heidemann’s efforts to catalogue and preserve the conversations he had with former Nazi leaders, many of whom he went to great lengths to track down in semi-hiding in South America, which first attracted Professor Weber’s interest.

“To understand Gerd Heidemann, we need to look beyond the Hitler diaries and even beyond his archive, he says.

“He was made and formed by war himself – aged just 14 when World War Two ended and it seems he spent the rest of his life he was trying to make sense of his childhood.

“As a journalist he took risks no one else was prepared to – spending months, and even years, covering conflicts in Africa and the Middle East.

“In the 1960s his editor at Stern set him the task of discovering the true identity of an adventurer, leftwing revolutionary and prolific author who wrote under a pseudonym. With few results he was moved onto another assignment but despite this Heidemann spent the next six to seven years pursuing him – he was simply unable to let it go.

“I think viewed through this lens the tenacity of Heidemann and the tactics he employed to befriend those who could give him first-hand accounts of this dark period of history begin to make more sense.”

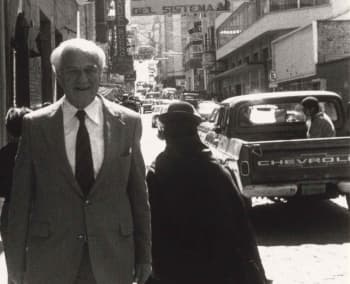

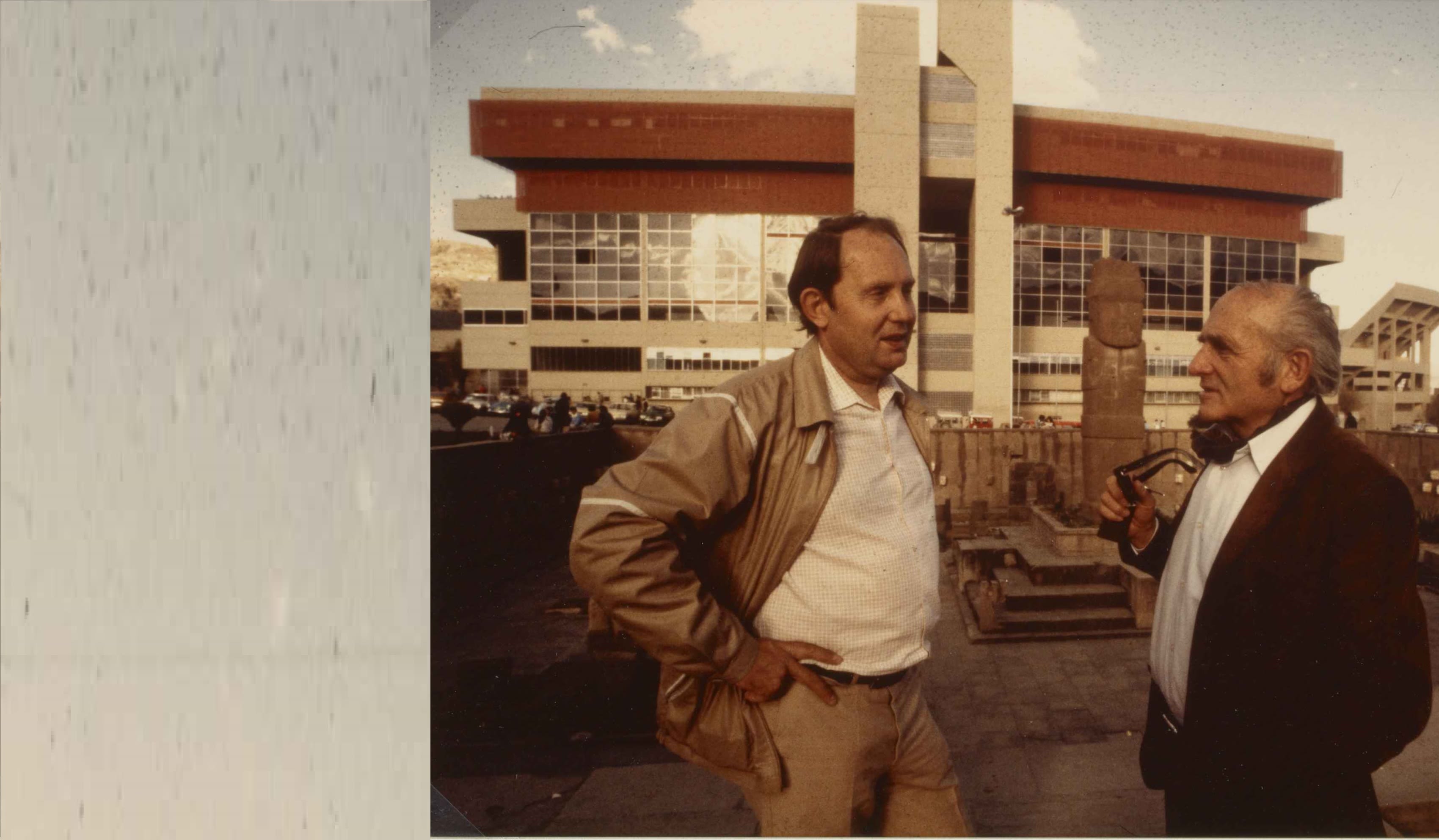

Gerd Heidemann reporting from Uganda

Gerd Heidemann reporting from Uganda

A remarkable collection chronicling war, revolution, and conflict

When Professor Weber was first granted access to Heidemann’s archive in 2015, he was unprepared for the scale of what he would find.

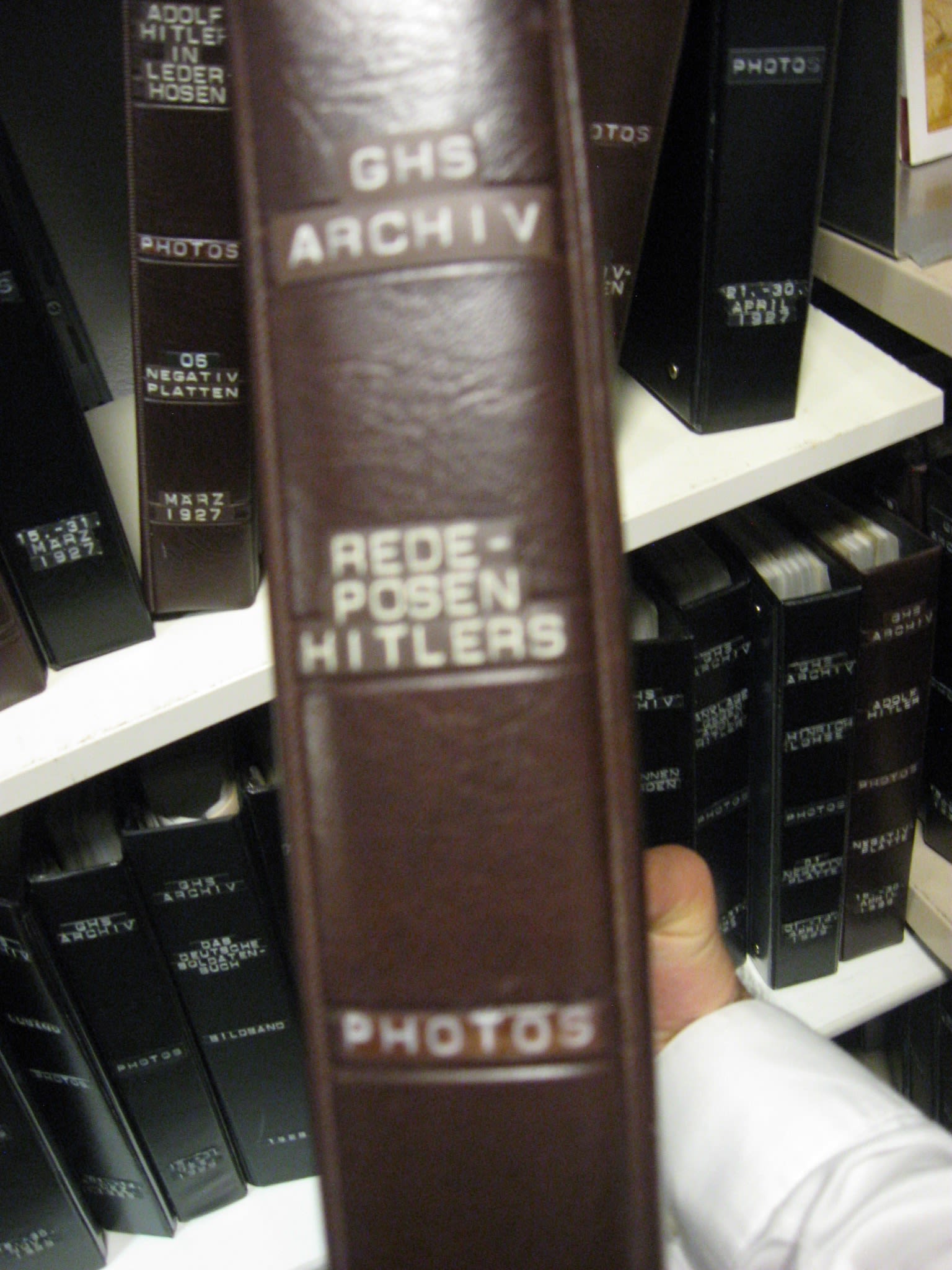

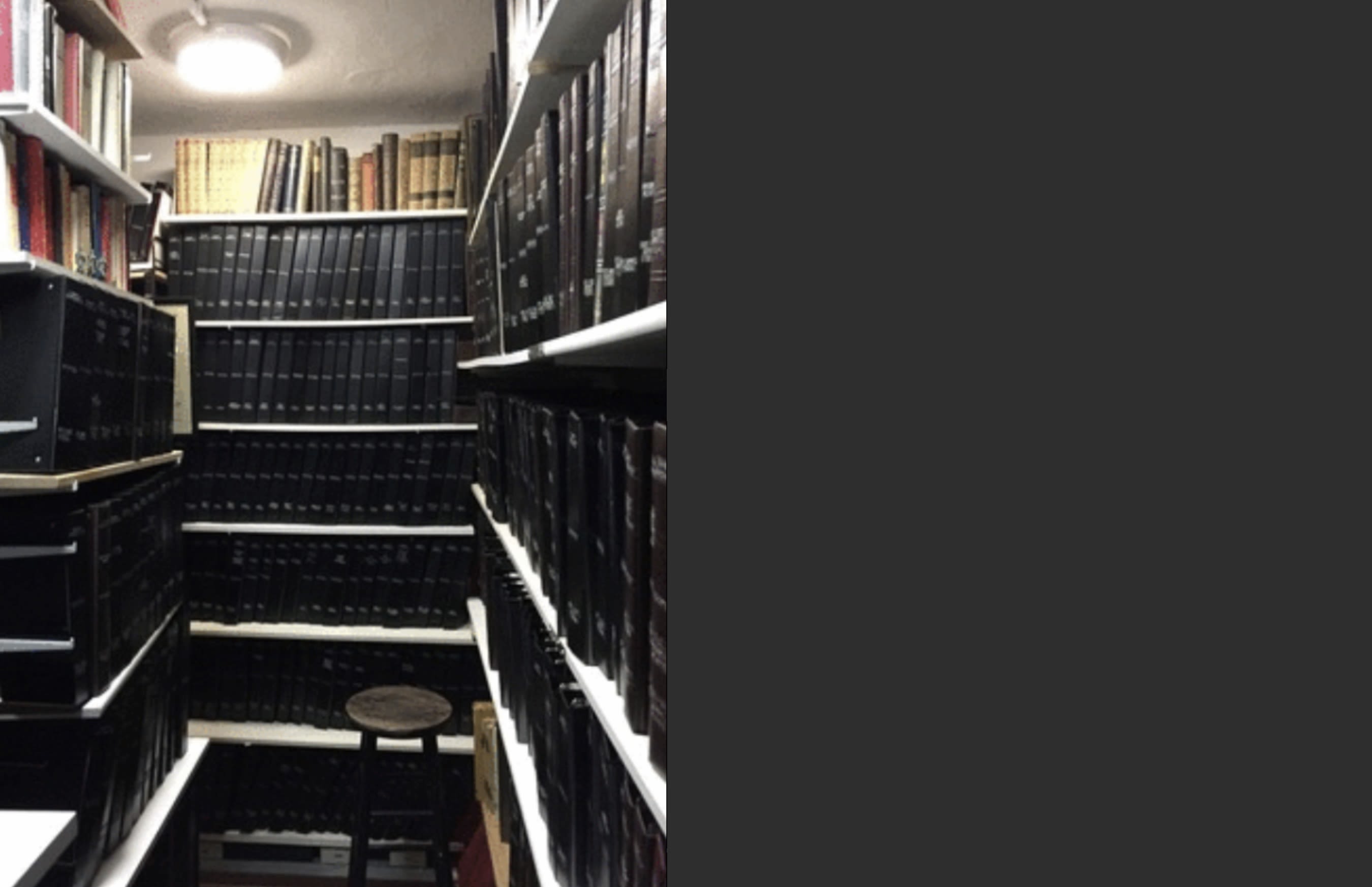

Every inch of the rented basement in a former tax office adjacent to Hamburg's Altona train station was utilised. Metal shelves with small walkways between them stretched as far as the eye could see, filled with over 7,300 meticulously labelled binders and all arranged chronologically.

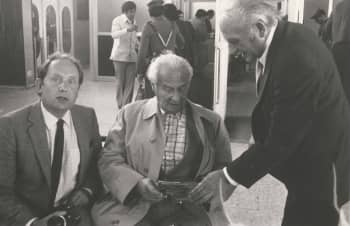

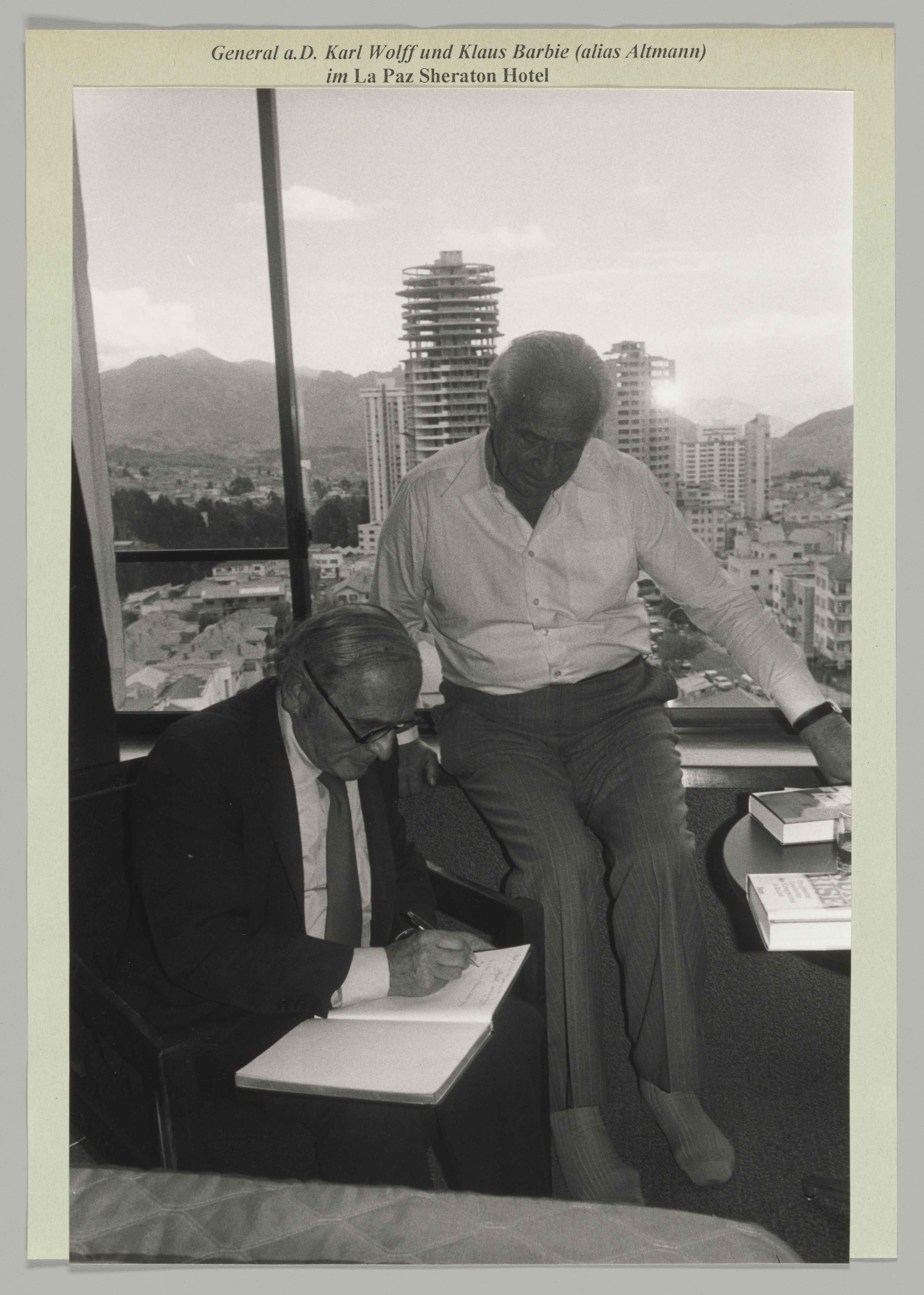

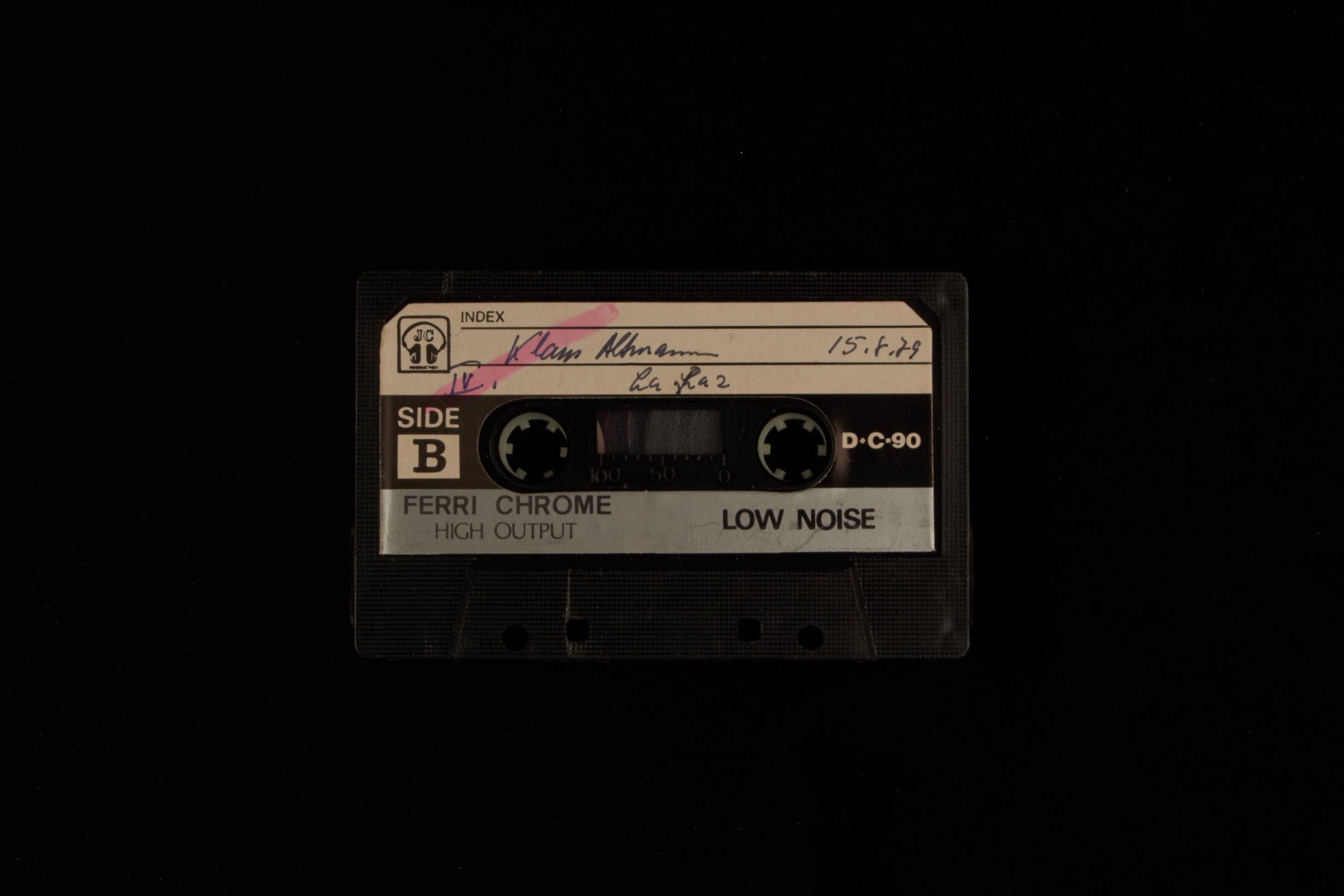

In addition to the folders of private documents, Heidemann had amassed more than 100,000 photographs and around 1,000 audio cassettes of taped interviews with protagonists of 20th century conflict, including former Nazi leaders such as Bruno Streckenbach, the head of personnel of the SS agency in charge of the Holocaust, Klaus Barbie, the 'butcher of Lyon' and former SS-General Karl Wolff, Himmler’s liaison officer to Hitler.

“It was remarkable to see the way Heidemann, then in this 80s, knew his way around every inch of his archive. He’d arranged it chronologically and could lay his hands on almost any file he mentioned”, Professor Weber explains.

“Despite the obvious issues with the Hitler diaries, it was clear that this was something remarkable. Heidemann has persuaded people in positions of power during the Third Reich to part with private documents never seen before and has obtained hundreds of hours of taped conversations in which they spoke candidly about the roles they had played in the War, the Holocaust and other atrocities.

“Of course, the obvious question remained, can we trust this information? Yet Heidemann himself was quick to address this issue. From the thousands of documents he could pinpoint those few about which he had doubts.”

Professor Weber was given access to any file he wanted to review and began work to verify their contents. He was soon satisfied that they were looking at a most significant collection and returned to visit Heidemann multiple times over the next decade, initiating conversations about how to perverse the resource for future generations.

Goering’s yacht and the web of Nazi contacts

As part of his mission to investigate former Nazis and to build his archive, Heidemann needed to win their trust.

This, says Weber, is where the complexities of his life – and the legacy of how he is viewed – comes into sharp focus.

“As the obituaries written in the weeks following his death demonstrated, many – and particularly in Germany – viewed him as a Nazi obsessive. Some went so far as to suggest he was a Nazi sympathiser.

“Throughout his life Heidemann was unable to correct this perception but I think the legacy of the collection he leaves behind reveals a very different side than that seen by the world while he was alive,” he says.

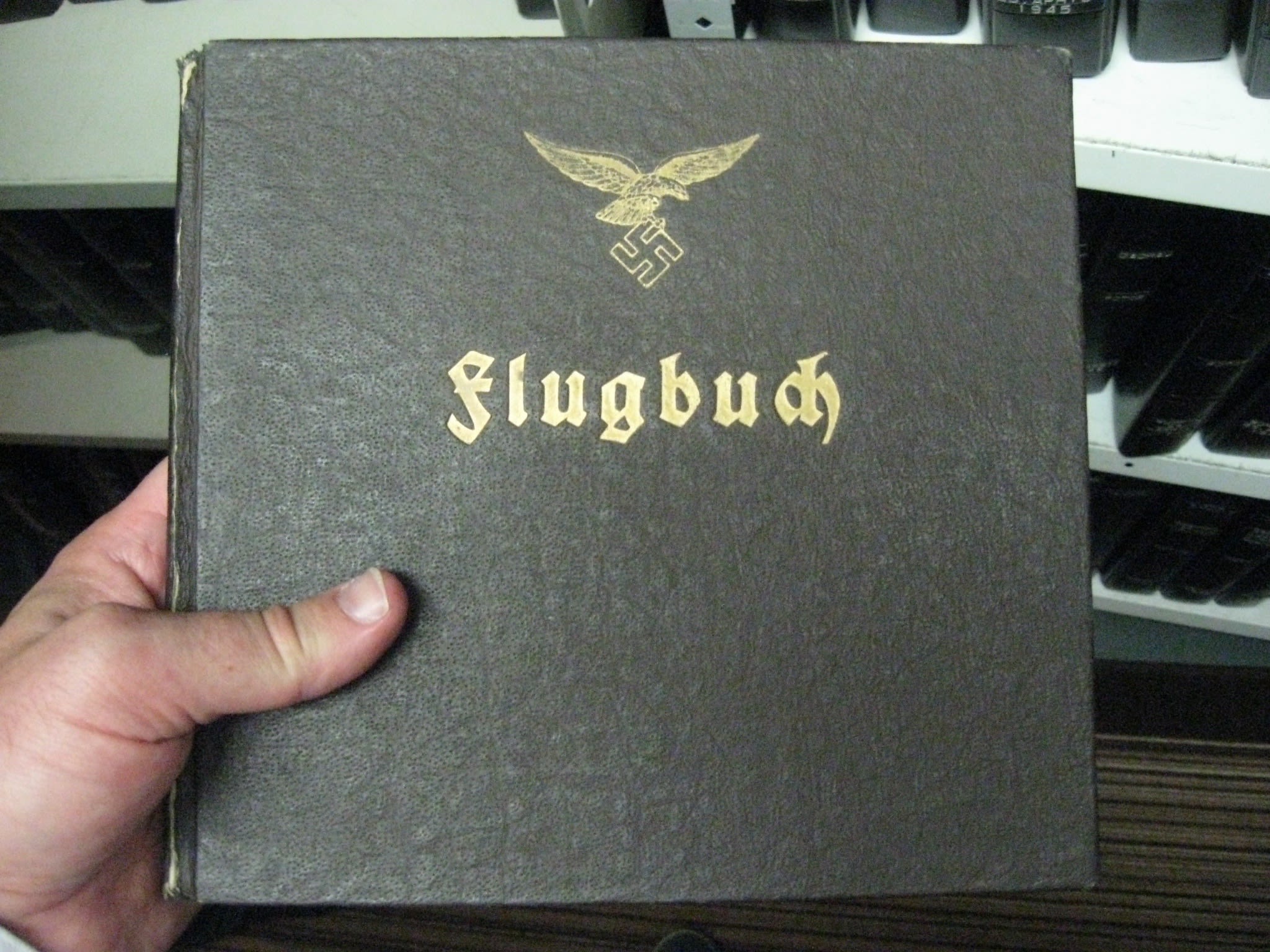

During the 1983 Hitler diaries scandal it was revealed that Heidemann’s trail to the documents began in 1973, with his purchase of a yacht, the Carin II, formerly owned by Hermann Goering, Hitler's air force chief.

It was on board the vessel that he first made contact with a number of Nazi perpetrators who would open doors to his South American endeavours.

When it was put up for sale again in 2004 the Jewish American outlet Forward in describing its history reported that ‘Heidemann turned the boat into a floating shrine to the Nazis’.

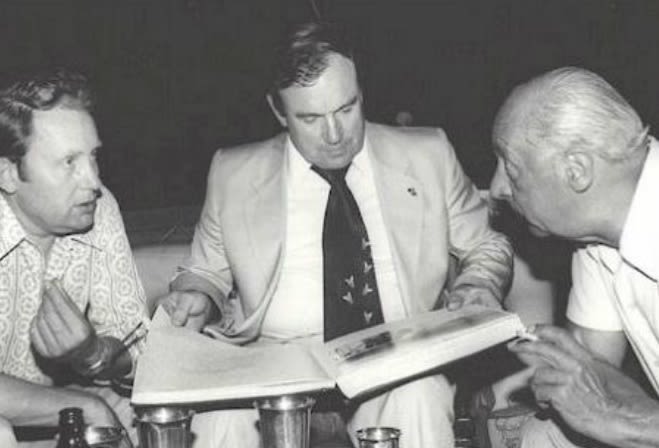

It is also documented through Heidemann’s own photographs that he used the Cairn II to reunite key Nazi perpetrators and to begin listening to their stories. At times, he brought them together with former resistance fighters or the American governor of Spandau (war criminal) prison.

Among those he met there was former SS-General Karl Wolff, Himmler’s liaison officer to Hitler, who would open many doors for Heidemann with others in semi-hiding.

In 1964 a West German court had sentenced General Wolff to life imprisonment for his part in the murder of 300,000 Jews, but he was released after seven years and remained in contact with his former party leaders.

“Heidemann managed to build trust between surviving members of Hitler’s entourage, high-ranking generals, and himself, initially utilising Goering’s yacht as a meeting ground,” Professor Weber adds.

“It was because they trusted him that many of them handed him their private papers and other documents and shared many of their secrets and their intelligence of the crimes of the Third Reich in conversations that Heidemann taped.

“The view that he was ‘one of ours’ allowed him to go where no one else had gone and to get his hands on material pertaining to this difficult chapter of the 20th century that otherwise would most likely have been lost forever.

“But the apparent closeness of these relationships was also his inadvertent undoing – making it very easy for others to paint him not as a serious investigative journalist but as an obsessive who was easily fooled.”

‘Zalusa’s’ mission to find Josef Mengele

Of all the horrors of the Holocaust, the name Josef Mengele still stands out as one of the darkest. Known as the ‘Angel of death’ the SS physician conducted inhumane, and often deadly, medical experiments of prisoners at Auschwitz. He was also the most notorious of the medical professionals who selected victims – usually those unable to work – to be murdered in the gas chambers.

After the war he evaded justice for his crimes and escaped to South America.

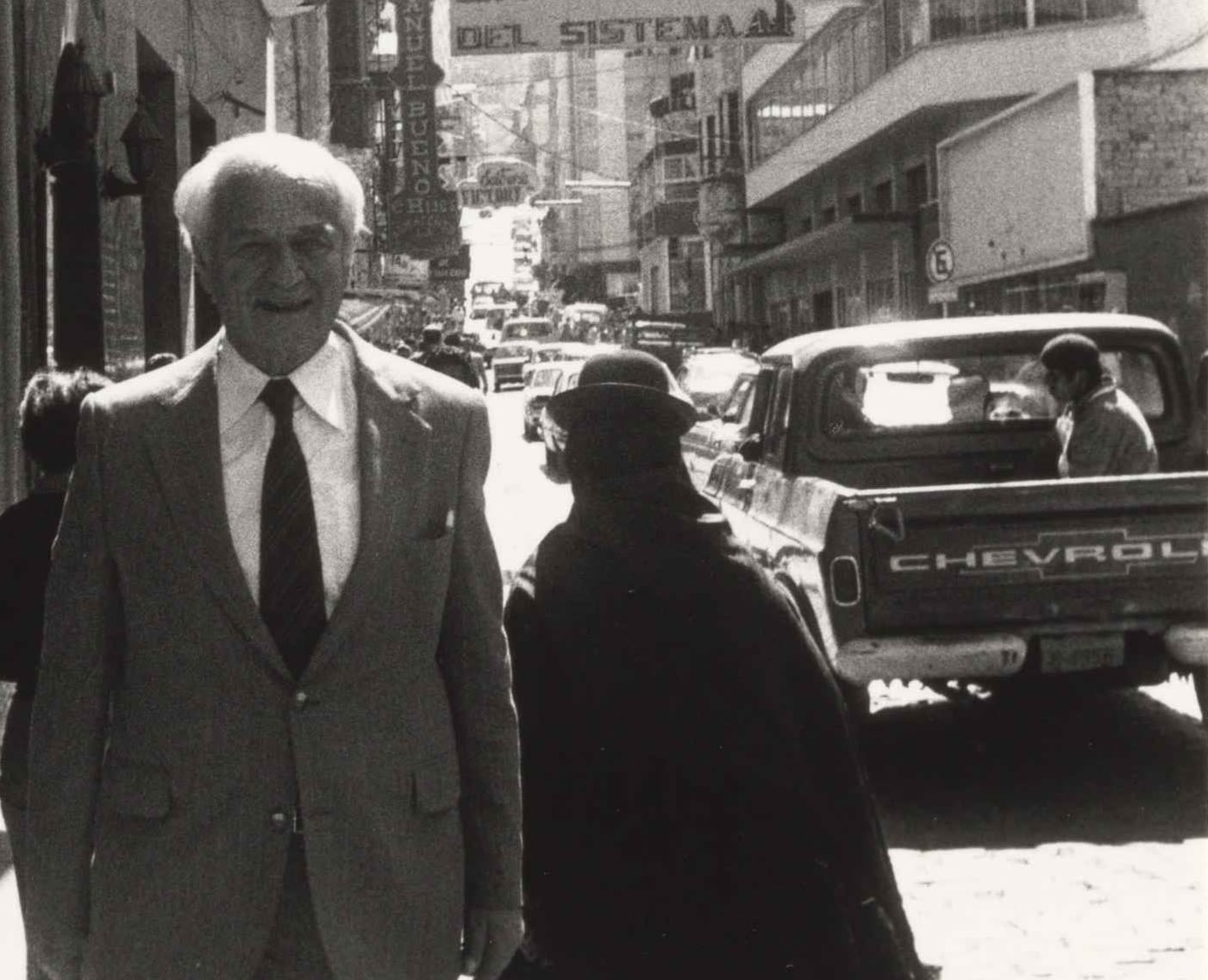

The Israeli intelligence service remained committed to finding him and in 1979 recruited an agent they named ‘Zalusa’ with high hopes that their new asset would finally lead to his capture.

With the full support and blessing of the Mossad, ‘Zalusa’ teamed up with former SS General Karl Wolff whose trust he had earned, in the expectation that Nazis in hiding in South America would open their doors to Wolff.

It emerged that Mengele had already died in an accident a few months prior to ‘Zalusa’s’ travels but he did not return empty-handed. He came back with taped conversations with approximately twenty-five high-ranking Nazis in South America, in which they openly spoke about their involvement in the crimes of the Third Reich as well as their lives on the other side of the world.

These included a thirteen-hour series of private conversations with Klaus Barbie, notorious as ‘the Butcher of Lyon’, in which he spoke openly about his experiences on the eastern front, how he personally put down the uprising in the Jewish ghetto in Amsterdam, how he turned members of the Resistance into collaborators, and how he received advance intelligence about the plans of Allied forces to land in Normandy.

What Heidemann could not say until the very end of his life – and which declassified documents verify – is that he was ‘Zalusa’.

“Throughout his life Heidemann kept this secret – knowledge which would perhaps have reframed how he was viewed,” says Professor Weber.

“He told me as he was nearing the end of his life that he worked with Mossad for more than 20 years both before and after the diaries debacle. Yet even when I had been able to ascertain this information from other sources as well, he remained fearful of breaking his vow of silence.

“This was not Heidemann’s only brush with intelligence services. Among the many other accusations laid at his door during his life was that he was an agent for the Stasi, the East German secret police and state security service.

“What Heidemann revealed to me in his advanced years, is that he did receive a Stasi approach but that he immediately reported this to West German authorities.

“They reportedly asked him to go along with it and to report back so he was effectively acting as a double-agent.

“During my investigations and conversations with Heidemann it became clear that just as the full spectrum and significance of his archive was unknown, so too was the true story of his life.”

A new home at Hoover

Professor Weber’s relationship with Heidemann began after the former Stern reporter had mentioned to a colleague and friend of Weber’s that he was getting old and that he had to start exploring a new future home for his beloved collection.

“The collection Heidemann had been building since the 1950s was undoubtedly one of the largest and most comprehensive private collections in Germany. As no official documentary evidence of many Holocaust-era atrocities in occupied eastern Europe has survived, it contains vital evidence that could finally shed light on crimes that have remained unresolved for the last seven decades,” he explains.

“But it was in the sole care of a man in his 90s in a rented basement adjacent to a train station. There was a real danger both of material being lost and that these important sources of information would be sold to private collectors and would never be seen again.”

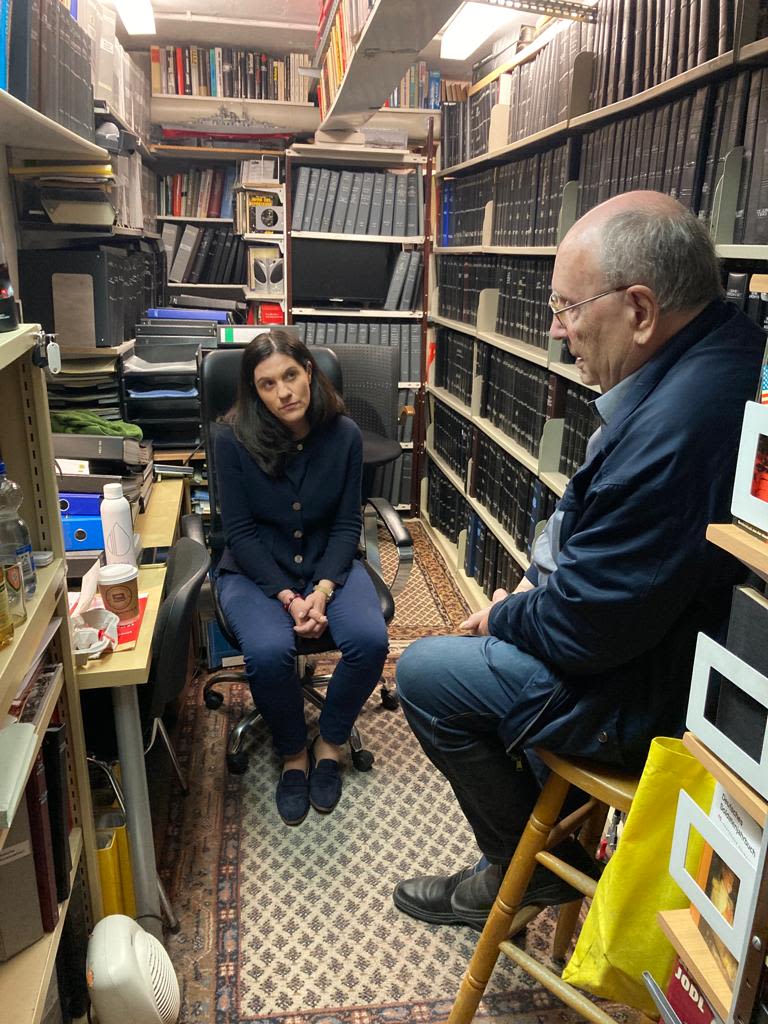

Professor Weber, who is also a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution, began to broker conversations between Heidemann and the research centre based at Stanford University in California. It boasts a vast library of more than a million volumes and an archive with over 6,000 different holdings.

The Hoover Institution, together with Professor Weber, went to great lengths to authenticate samples from Heidemann’s Collection before coming to a final agreement that they would be prepared to become its custodian.

Hoover staff including Taube Family Curator for European Collections Katharina Friedla began visiting his basement to learn more about his chronological ordering and the material and to begin making arrangements for the transfer. It was then in the summer of 2023 that the collection was acquired by the Hoover Institution. It then took several months to move the collection securely from Hamburg to California.

Hoover archivist Katharina Friedla with Gerd Heidemann in his basement archive

Hoover archivist Katharina Friedla with Gerd Heidemann in his basement archive

Since then, extensive work has been underway to open up the Heidemann collection to historians, scholars and the public.

The 800 cassette tapes Heidemann carefully arranged on his basement shelves have been digitised, transcribed with AI software and translated into English making them freely available to all those with an interest in this period.

The newly release tapes show that while being recorded by Heidemann, Barbie and other Nazi war criminals boasted openly of what they had done, assuming they were speaking among friends.

“The recordings pull away the rug under the lies that Nazi perpetrators told in postwar court rooms,” Professor Weber says.

“In one interview conducted in Germany Heidemann managed to get Bruno Streckenbach, the head of personnel of the Reichssicherheitshaupt within the SS to reveal how SS perpetrators and their lawyers had lied in court rooms in a coordinated fashion about their role in the ‘Holocaust by Bullets’, which resulted in the death of 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews,” Weber says.

“We know far too little about what was going on in heads of Nazi perpetrators as in Court they would always play down their role.

“This is the most comprehensive release of first-hand material in decades – a real treasure trove and we have only just begun to scratch the surface of the secrets like this that it may hold.”

The archive prepared for transport

The archive prepared for transport

A once in a lifetime opportunity to understand extremism

Professor Weber says one of the most striking elements of the material gathered by Heidemann is that even decades on from the downfall of National Socialism in Germany, those he interviewed remain committed believers.

“When it comes to the first-person perspective of top Nazis and of extremists we generally have to rely on Court testimony but in this scenario they have an interest to downplay their roles.

“Here we have members of Hitler’s inner circle sharing their thoughts, feelings and recollections in an unguarded and unfiltered manner.

“They are presenting themselves in the way they believe the world should see them and that is really important in trying to understand extremism both then and now. It will provide research material for many decades to come.”

Already parts of the collection have inspired a film and several new documentaries. Professor Weber has worked with the filmmaker Foeke de Koe providing expert commentary and advise for a primetime one-hour documentary on Dutch TV (NPO2/WNL) titled ‘Barbie Tapes’ which explores the sound recordings of the SS officer talking extensively about his war crimes in Amsterdam.

A six-part podcast series has also just been released, including one on Willem Sassen, a leading Dutch SS propagandist during WWII, who reinvented himself after escaping from prison in dramatic style at the end of play he had put on, making his way to South America where he became PR adviser to the Peróns. He is most famous for having managed to get Adolf Eichmann, the administrative brain behind the Holocaust, to admit on camera to his ideological commitment to National Socialism and its crimes, unlike in court where he pretended to have non-ideological in nature.

Heidemann’s taped recordings from 1979 reveal Sassen as someone who still admired Goebbels and Hitler and in his own words he gives his account of visiting the Warsaw ghetto in which he blames the Jews for the conditions, talks derogatively about the Jewish character and of how they had supposedly provoked Auschwitz. And they reveal him as someone not so very different to Adolf Eichmann.

“This collection is the story of how many leading Nazi perpetrators lived their lives in the four decades following the war. It helps us understand how they looked at the past, tried to find a new places in a postwar world, and how they imagined the future,” Professor Weber concludes.

“It is also the story of an intrepid reporter who chronicled conflicts worldwide and whose unseen photos and documents will allow us to get a much better sense not just of the crimes of the Third Reich but also of many of the wars and conflicts of the Cold War era.

“On Heidemann’s motives and character, views are likely to continue to differ but on the importance of his archive, there is much greater consensus. The Heidemann Collection promises to shed new light on some of the most fundamental unresolved questions about the Third Reich and the Holocaust, including Hitler’s own role in the Shoah.”

Historians can now begin to sift through the ‘new trove of material’ that will allow them to study in greater detail than ever before the first-person perspective of the radicalization and crimes against humanity by extremists, something Professor Weber says is absolutely vital at a time at which the world once again is starting to give in to the lure of extreme political behaviour.

“In line with new breakthroughs in the study of extremism, we need triangulate the inner lives of extremists against other evidence relating to their behaviour”, he said.

“As Dutch scholar of extremism Rik Peels has said, ‘extremists are also people who act from convictions, for reasons, who have intentions and goals, who think and reflect and make difficult choices. To truly understand and explain radicalization, we must not only look at all kinds of factors that transcend them, but also at what they themselves bring to the table when they explain their beliefs and actions.

In this clip from Foeke de Koe's 'De Barbie Tapes' documentary for WNL, University of Aberdeen Professor and Hoover Institution visiting fellow Thomas Weber speaks about the importance of German journalist Gerd Heidemann's undercover conversation with Klaus Barbie in 1979 - now held in the Gerd Heidemann Collection at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University - for understanding the nature of extremism.