Celebrating our foundation as a ‘light of the north’

Every year in February the University marks Founders’ Day – a celebration of the legacy of Bishop William Elphinstone and his vision to create a university as a ‘light for the north’.

But who was Elphinstone? Why was Aberdeen an early beacon for education, formed at a time when only Oxford, Cambridge, St Andrews and Glasgow were already in existence?

And how did he persuade both a king and a pope to support his plans to draw the best and brightest minds to north-east Scotland?

A man of many talents

William Elphinstone was a greatly respected man in his day, a man who worked in many spheres – a clergyman and a scholar who was also a notable lawyer and senior diplomat. But at the heart of his work, after he became bishop of Aberdeen in 1483, was the good of the local community and that of the wider kingdom of Scotland ruled from 1488 by his royal master James IV.

Throughout he was a champion of the Renaissance, a man of the international humanism of the time, known as the ‘New Learning’– he sponsored the introduction of printing to Scotland, and his personal library contained a large number of early printed books, or ‘incunables’. The University which he founded in Aberdeen was intended to be a beacon of the New Learning, a light for the north.

Accompanied by investments in local bridges and church-building, and the compilation of the first national collection of saints’ lives, it was the University that was at the heart of his project. Having the ear of the king and the pope, he shared his dream to see a place of learning where, in the terms he used to make his case for support, "men who are rude, and ignorant of letters" could receive an education. This would supply the country’s growing need for trained lawyers, doctors, scholars and priests who would be qualified to study and teach at any university in Europe.

The founding of a university

Elphinstone received Papal permission in 1495 to found a university, the institution which in 1505 was accompanied by the foundation of a college, later named King’s College for King James IV. This is the origin of what is today the University of Aberdeen.

Despite these achievements, to the majority of people in Scotland, Elphinstone remains to some degree an unknown figure.

Professor Jackson Armstrong, Chair in History at the University of Aberdeen, said: “Bishop William Elphinstone was a leader at an exciting and dynamic time in the intellectual, legal, and ecclesiastical world of fifteenth-century Scotland. Far from being the ‘dark age’ it was once thought to be, Elphinstone’s energy and influence was part of what brought Scotland in the later middle ages right to the forefront of European progress.”

Born out of wedlock in 1431, Elphinstone was brought up among clerics in the shadow of Glasgow Cathedral, and he followed his worldly father into the priesthood.

Elphinstone graduated from Glasgow University in 1462, continuing his studies in canon law for a further three years. Like his clerical father before him, he then completed his studies abroad at the universities of Paris and Orleans.

Clerics formed more than the backbone of the Scottish judicial system in the fifteenth century: major crown servants were often drawn from among educated churchmen. Shortly after Elphinstone returned home in 1471 – called back to become the chief officer of the diocese of Glasgow – he was recruited to the royal council, eventually emerging as a diplomat and senior negotiator of royal treaties. Titles, honours and further duties followed. As well as becoming Bishop of Aberdeen, Elphinstone served variously as Chancellor of the Kingdom of Scotland, keeper of the Privy Seal and Commissioner of Crown Lands.

A lasting legacy for the region and the nation

After standing down from his government position as Chancellor of Scotland in 1488, he turned his talents to the internal reform of his diocese. As rector of St Nicholas in Aberdeen, Elphinstone organised the funds to complete the choir and he also carried out building and works at St Machar’s Cathedral, completing the central tower with a steeple like that at St John’s in Perth and furnishing it with three bells weighing 12,000 lbs.

Although it was not completed in his lifetime, Elphinstone established preparatory work for constructing the Bridge of Dee. He ordered the collection of building materials and bequeathed money to finish the project after his death, a task that was overseen by his successor Bishop Dunbar in 1529.

He also did much to reform the religious life of Aberdeenshire, and made the cathedral canons into a community of well-educated and effective priests.

The civic records of Aberdeen detail various features of relations between the neighbouring royal burgh and the Bishop, and the town council and magistrates were keen to keep in his good graces. In 1509, for instance, they made a gift to him of fine wines, wax and spices.

The Bishop was deeply concerned with questions of law and advocated the education of all eldest sons of the nobility in the law, leading to an act of parliament for this purpose in 1496. Once the Papal Bull for his new University was granted, Elphinstone moved to draw in the best and brightest teachers. Typically, in an age when it was the rule for only priests to teach, the bishop was open to the appointment of anyone with talent.

His curriculum was no less ambitious. In addition to training lawyers, clerics and administrators, so vital in the development of the government of the kingdom, Elphinstone also ensured – through the provision of a university mediciner – a flow of doctors, too.

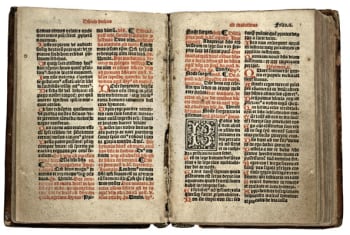

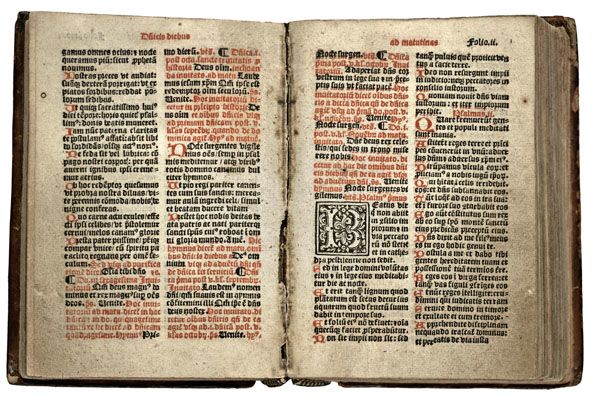

But arguably his greatest legacy, not just to the university but to the nation as a whole, was the introduction of the printing press to Scotland, first used to publish the Aberdeen Breviary (a book of daily prayers) for the church throughout the country.

The Aberdeen Breviary was compiled under the direction of Bishop Elphinstone and was designed to be recited by the Scottish clergy throughout the liturgical year. But its major achievement was the compilation of the lives of saints from across the kingdom, assembled into a national prayer book. This was in itself a significant research projected coordinated by Elphinstone.

The country's first printers, Walter Chepman and Androw Myllar, were granted a patent by James IV in 1507 to set up in Edinburgh to 'bring home a printing press ... for printing within our realm'. They printed a number of literary works popular at the time and, in 1509-10, the press produced a two-volume edition of the Aberdeen Breviary.

“The Gutenberg printing press was only invented during Elphinstone’s lifetime but being a man of letters he was deeply aware of the significance of this new medium of communication and was instrumental in bringing the first printing press to Scotland, and with the Aberdeen Breviary producing Scotland’s first full-scale printed book” said Professor Armstrong.

The University marks its creation through Founders’ Week celebrations. To find out more and to book your place visit https://www.abdn.ac.uk/events/founders-week/