The craftsman professor who transformed science teaching

Patrick Copland (1748 to 1822) was an Aberdeen professor and celebrity of his day who corresponded with some of the best-known names in science.

His legacy today can be felt in our classrooms and in our accepted approach to science teaching and lifelong learning, but his name is little known.

On the bicentenary of his death we look at the five decades he spent as a University professor and his many contributions as a craftsman and inspirational teacher - and his unorthodox reputation which had some convinced he was a 'magician' who carried lightning in his pockets!

Changing the face of science teaching

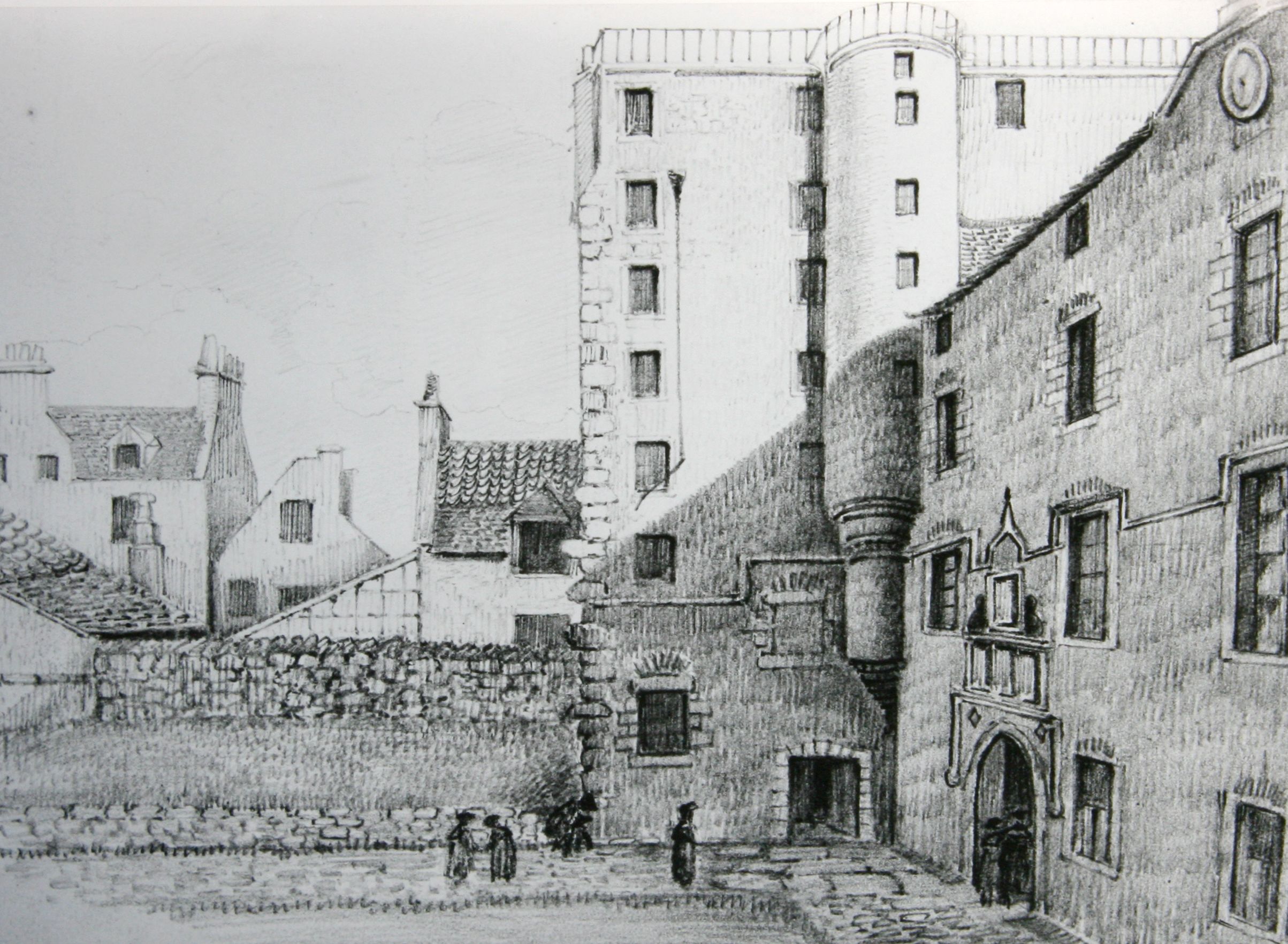

Patrick Copland was born in 1748 in a small parish to the north-west of Aberdeen and educated locally before being accepted at the age of 14 to study at Marischal College (which later merged with King’s college to become the University of Aberdeen).

In 1774 George Skene, Marischal’s professor of natural philosophy who had taught Copland as an undergraduate, made the unusual step of deciding that he needed an assistant and Copland was appointed to the role.

A year later, when Skene took on the professorship of Civil and Natural History, Copland stepped up and remained a professor at Marischal until he died in November 1822.

But while his education may have been local, his outlook was not and over his decades in post Copland widened the horizons of both Marischal college students and the citizens of Aberdeen and grew the role of science in society.

Copland’s passion was Natural Philosophy, in particular its application to everyday life, to agriculture, to manufacturing, to engineering.

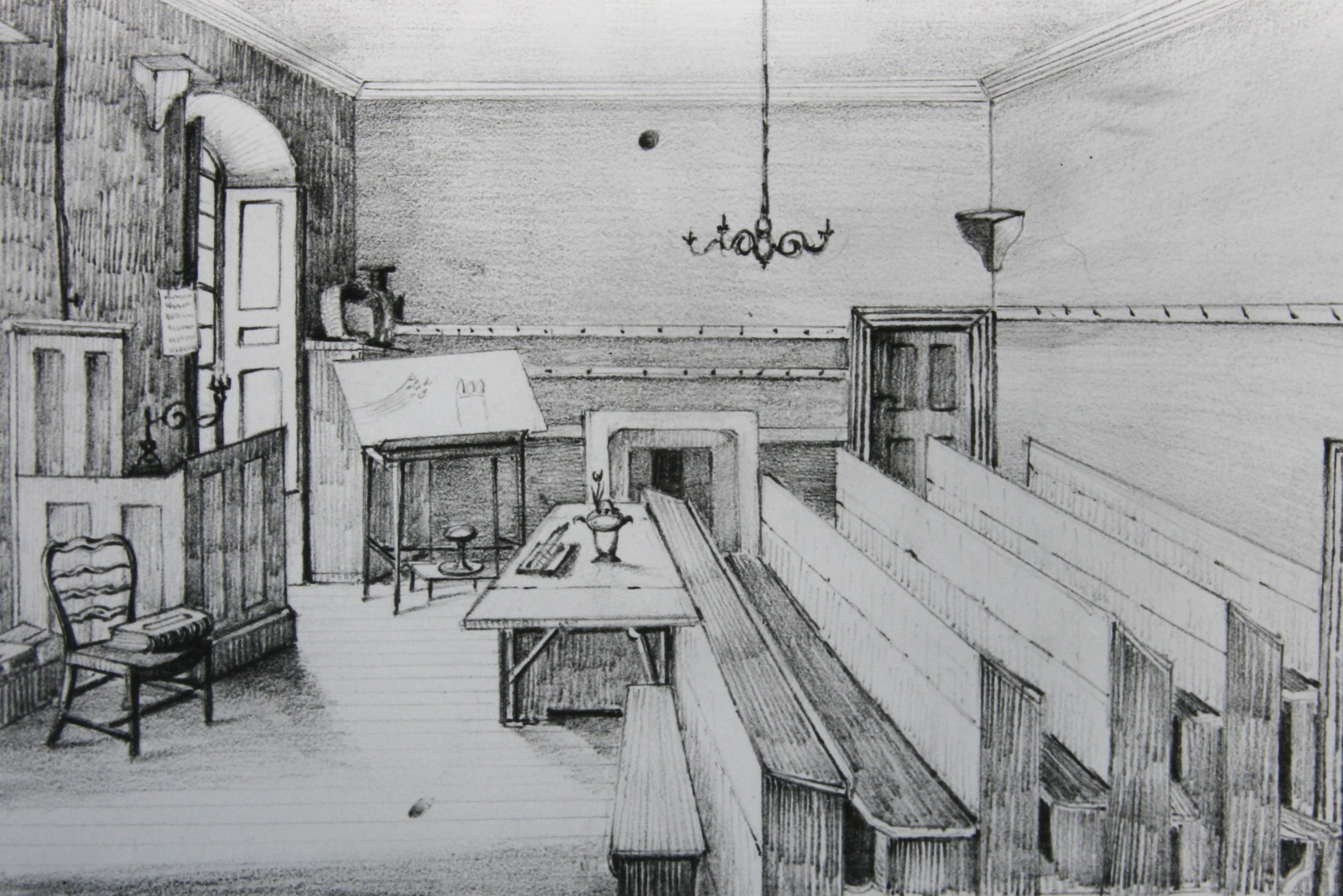

Unlike other professors of the time, who generally dictated notes to students, Copland wanted to demonstrate the use of science, which at the time was taught to students through the subjects of Natural History, Natural Philosophy and some branches of Mathematics.

While the experiments of Galileo, Newton and others were discussed at universities, teaching with practical demonstrations was not ubiquitous as it is in schools today. Marischal had a paucity of such equipment and Copland quickly set about changing that.

The craftsman professor

When Copland took over the teaching of Natural Philosophy in 1775 the value of the College’s philosophical and astronomical apparatus did not exceed 70 guineas and in his own words was ‘in great disorder and extremely defective’.

With a strong interest in practical mechanics, Copland got to work.

In just a few years he had repaired all of the old machines and executed several new ones. Teaching by demonstration soon became Copland’s trademark. One former Marischal College student Edward Ellice, who became Secretary of State for War in the 1830s, described Copland as "The man who more fully opened the eyes of the student to this world than any teacher he had ever met".

But building such instruments was not without cost and Copland was quick to recognise the importance of fundraising to universities.

Applying for grants was not the way forward in the 18th century but it was a step Copland took. He repurposed his interest in models of machinery, tapping the local union of artisans, the “Seven Incorporated Trades” for 5 guineas “towards purchasing the machines wanted for the Marischal College” in 1780 and a year later he drew up a public appeal in the name of the College for astronomical equipment.

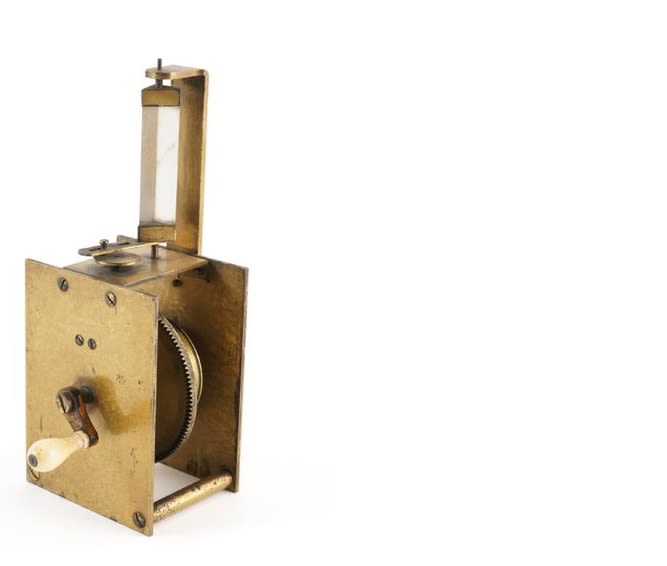

In 1783 he applied to the Board of Trustees for the Encouragement of Manufactures in Scotland, securing a grant of £50 per year. Copland used this to employ John King, who had just finished his watchmaking apprenticeship, and installed him in the College to help him make models of machinery.

King, who stayed on until around 1790, has been proposed as the first ever university technician and over the years worked with Copland to produce hundreds of demonstration pieces.

Their work in wood, metal and glass was said to be indistinguishable from the best instrument makers and apparatus was described at the time as ‘the most complete and extensive’ in the UK.

An inventory made at the end of Copland’s career included over 500 entries, mainly for demonstration apparatus.

Educating the masses

A decade into his teaching career Copland branched out from the privileged walls of the University to offer his courses to ‘artisans in the mechanical profession’ through a series of public lectures which began in 1785.

Copland’s charge of 1 guinea for the course was about a week and-a-half’s salary for a journeyman, no mean fee but small compared with the cost of lectures aimed exclusively at gentlemen and ladies.

On average they attracted around 60 attendees and were so popular that they ran for 27 years.

But Copland’s public lecture series, together with an earlier venture to equip the Castlehill Observatory with modern instruments and to make it a semi-public space, earned him an interesting reputation in the city and beyond.

A private letter to another of the Marischal College professors suggests that Copland acquired or cultivated the image of a bit of a magician as it stated: “The thunder and lightning are in general attributed to the Hocus Pocus tricks, which Professor Copland has lately been playing at the observatory and elsewhere. ... The mob are greatly incensed against him, the very women would surely attack him in the streets, were it not for a small vial of Electrical matter, which he is said to carry about in his Breeches pocket”.

This statement likely referred to electrical equipment like Leyden jars and sensational demonstrations involving administering electric shocks to students.

His unconventional reputation also extended to his personal life. For a time he was known as ‘the principal beau in Aberdeen, with his smart dress and colourful clothing often remarked upon’.

Nevertheless, he remained a bachelor until he was thirty-nine, marrying Elizabeth Ogilvie in September 1787 who was almost twenty years his junior.

Copland invented his ‘head of despair’ to demonstrate the phenomenon of static electricity. The hair is woven into a tinfoil scalp, connected to the base of the head by a metal rod. When placed on an electro-statically charged table, the hair stands on end creating an expression of shock and despair.

Copland invented his ‘head of despair’ to demonstrate the phenomenon of static electricity. The hair is woven into a tinfoil scalp, connected to the base of the head by a metal rod. When placed on an electro-statically charged table, the hair stands on end creating an expression of shock and despair.

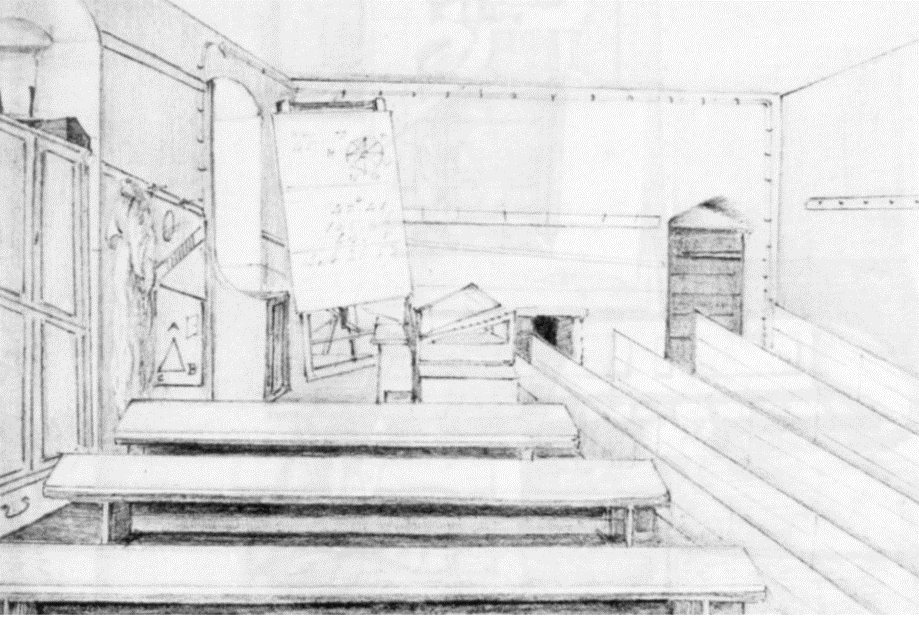

Sketch of a Marischal classroom likely to have been used by Copland

Sketch of a Marischal classroom likely to have been used by Copland

A lasting legacy often overlooked

In addition to the creation of the Castlehill Observatory and his popular evening classes, Copland’s influence on the region further extended to a role which might now be called a consultant physicist.

He advised the town on obtaining improved fresh water supplies, and in 1804 put forward proposals for what would have been one of the very first municipal sand and gravel slow filtration beds, had it been implemented.

He also gave advice on standards of length, weight, and volume measure, and made accurate comparative determinations for them. He advised town and county on matters of surveying, and made the earliest measurements of the height of the Deeside hills by barometric means.

He was a personal friend of the 4th Duke of Gordon with whom he had a regular correspondence about their mutual interest in mechanics and astronomy for over 40 years.

In 1787 the Duke invited Copland to accompany him on a tour through France and Switzerland. They were away for 3 months visiting Chamonix and Geneva where he learned about the process of bleaching by chlorine. This he subsequently introduced into this country with the assistance of two Aberdeen bleachers.

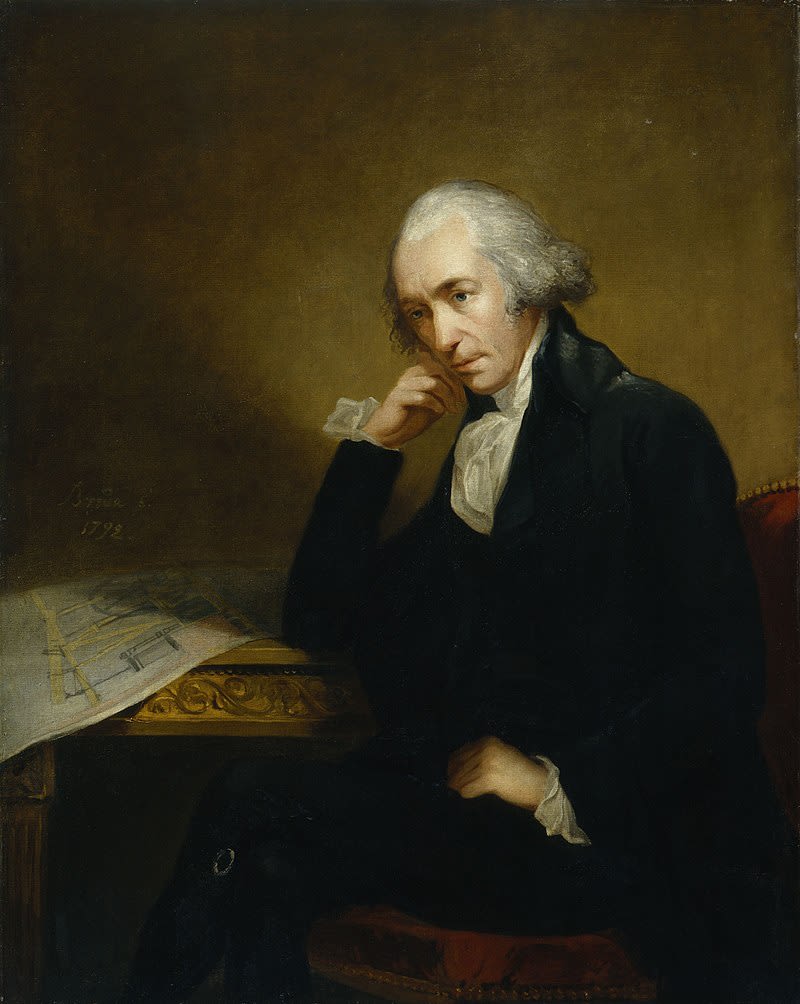

During his lifetime Copland was in frequent correspondence with many of the great minds of the day including the Scottish inventor James Watt, engineer Thomas Telford, and geologist and agriculturalist James Hutton.

He was a member of many learned bodies and a founding Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Thomas Telford was clearly impressed by Copland, with whom he corresponded on several subjects in 1801/1802, remarking in a letter: “The country owes you much for the good you have done especially by your judicious lectures accommodated to the capacities of Mechanics, and your ingenious experiments. This mode ought to be adopted in every seminary of learning.”

Similarly one of his former pupils, Neil Arnott, who went on to forge a career as a successful doctor, physician to Queen Victoria and as a social reformer made mention of him in his introduction to his work Elements of Physics. Here he wrote: “But there is a change taking place in the world, connected closely with the progress of science, yet distinct from it, and more important than half of the scientific discoveries – it is the diffusion of knowledge among the mass of mankind”

Despite Copland’s celebrity status in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as the decades passed and with it those whom he had taught, his name declined into undeserved obscurity for he had published nothing on his course nor on his apparatus.

As the bicentenary of his death is marked, it is Copland’s own correspondence and the impressive collection of apparatus he amassed which enables his story to be shared once again.

The University’s Special Collections is home to many of his letters and much of his equipment. This will be showcased at an event celebrating his life and achievements on the bicentenary of his death, November 10, 2022.

James Watt

James Watt

Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford

James Hutton

James Hutton

Article produced from the extensive research of Dr John S Reid. A collection of his many papers and essays on Patrick Copland are available at https://homepages.abdn.ac.uk/npmuseum/articles.shtml