2. Chapbooks and Chapmen

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary

Our twenty-first-century world has little awareness of the chapbook phenomenon of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, perhaps because these small books, pamphlets and tracts have no direct modern comparisons. These small and affordable paper items were often hand printed and always unbound, and were made from the folding down of a single large sheet of paper. They were the stock and trade of chapmen, who travelled the country on horseback or on foot, usually in geographical beats, knocking on people’s doors or setting up stalls at markets and fairs. Sometimes they were sold directly by printers. Thousands of items like this were published in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and they are evidence of growing literacy among ordinary people.

They also frequently contain woodcut images that not only made such items more visually enticing, but also attracted non-literate audiences. Such items of street literature were designed to be ephemeral. They were printed on low quality paper and sold for pennies. We might think of chapbooks as the equivalent of the newspaper, magazine and gossip column culture of the day.

All of this engineered a situation where chapbook survival rates are low. Indeed, evoking the practice of wrapping a fish supper in newspaper, in his 1818 novel The Heart of Mid-Lothian Scott describes a chapbook being recycled as the wrapping for a ‘muckle cheese’ that is sent as a gift to the novel’s principal character, Jeanie Deans! This makes the sheer volume of such items preserved at Abbotsford all the more remarkable.

Chapbook collections can reveal a great deal about the reading habits of the day and the type of content that was consumed by ordinary people, individuals who are so often invisible in the historical record. It would be reductive to think of the reading appetites of this period purely as Romantic or antiquarian. The masses, where they were reading at all, were often reading chapbooks, broadsides and tracts.

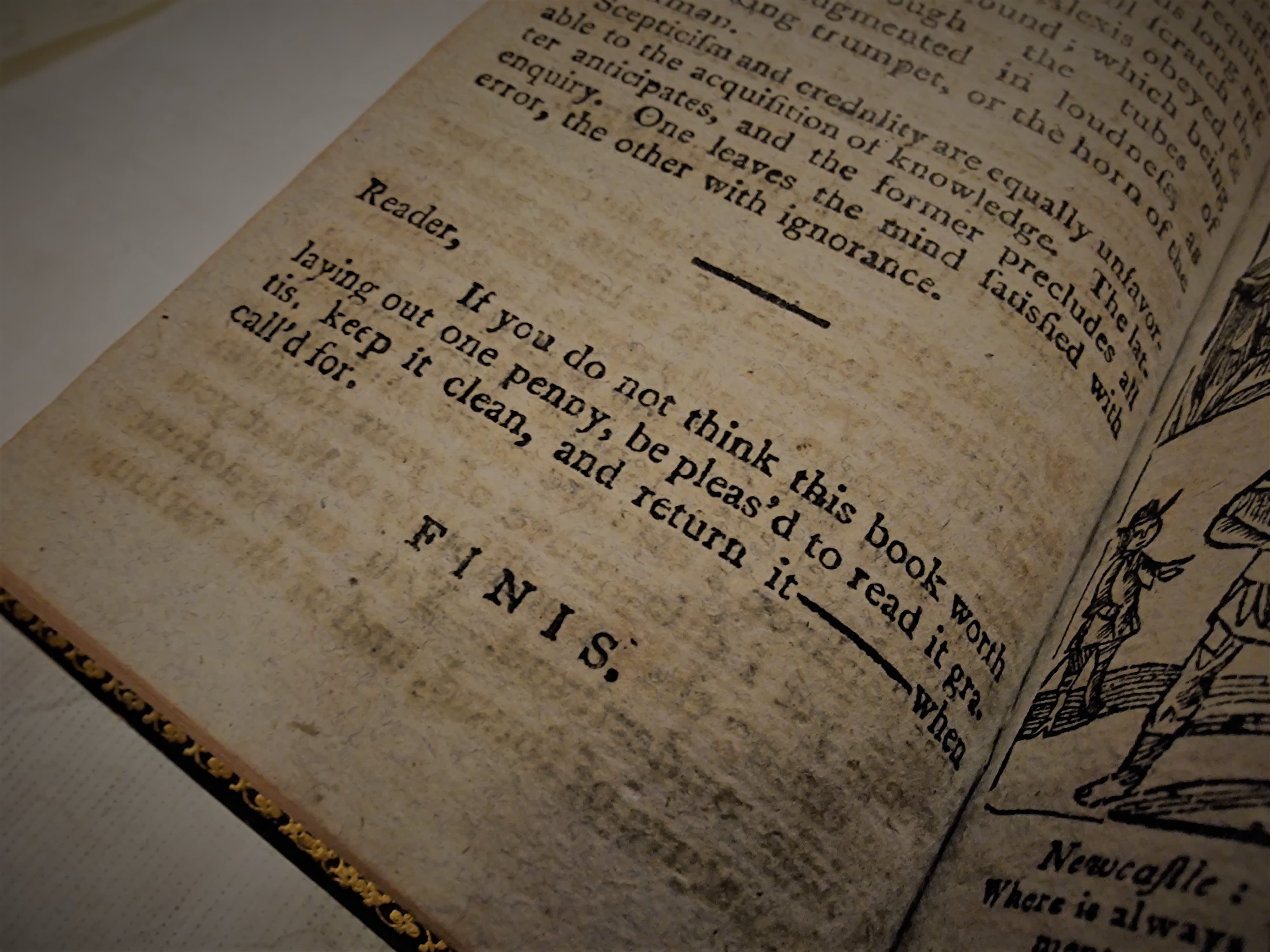

Scott’s collection tells us a good deal about how these kind of items were circulating in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The chapbooks themselves often contain additional snippets of information revealing how they were being bought and received by the public, and what a consumer should do if they found the product wanting!

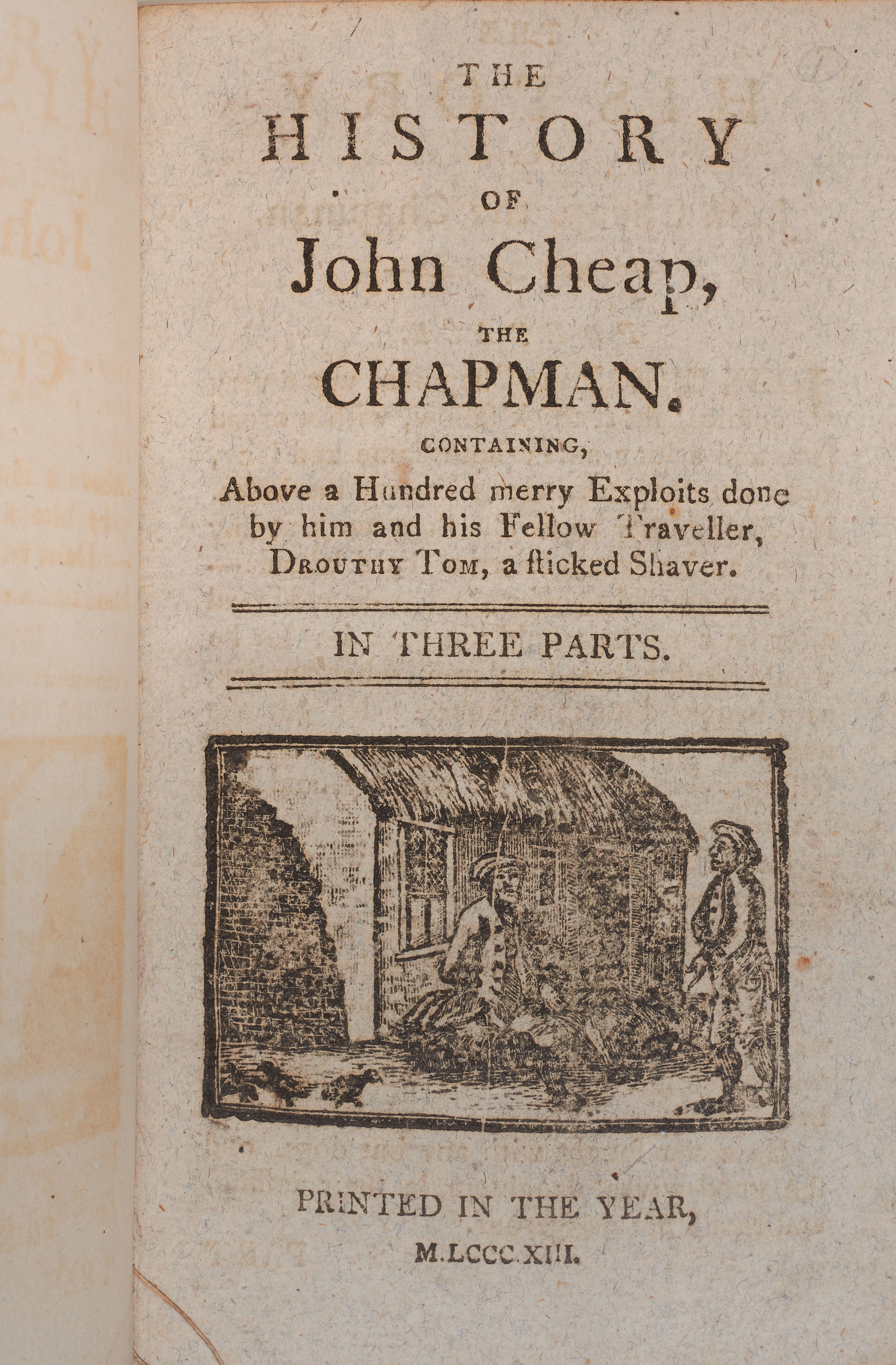

Perhaps one of the most evocative windows on the world of chapbooks and chapmen, comes from a chapbook itself, bound within a volume titled Popular Tracts. Here, we are introduced to the character of one of the few chapmen preserved in literature, John Cheap. You can find a description of John Cheap here:

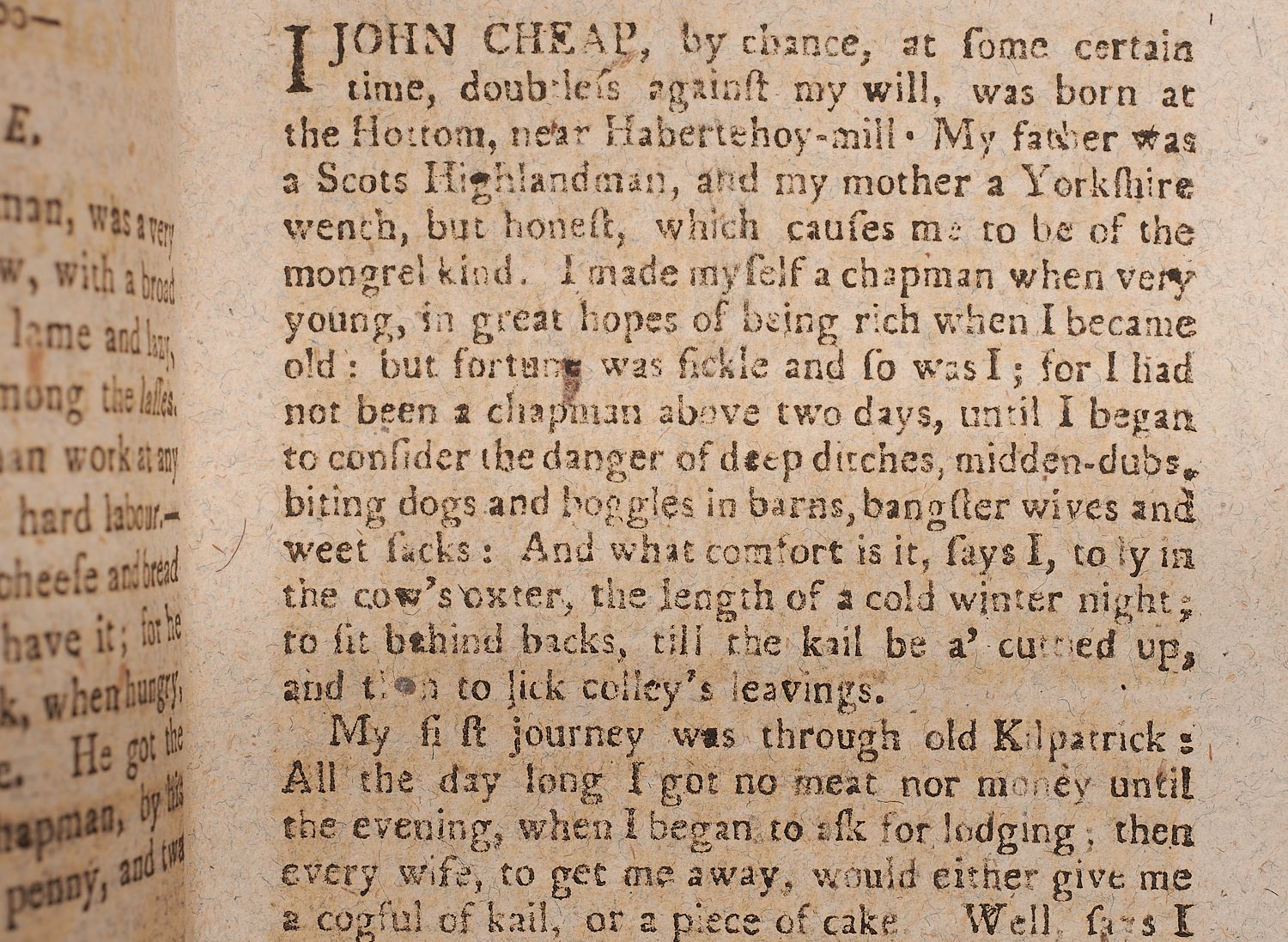

And listen to his story in his own words:

‘I made myself a chapman when very young, in great hopes of being rich when I became old: but fortune was fickle and so was I; for I had not been a chapman above two days, until I began to consider the danger of deep ditches, midden-dubs, biting dogs and boggles in barns, bangster wives and weet sacks: and what comfort is it, says I, to ly in the cow’s oxter, the length of a cold winter night; to sit behind backs, till the kail be a’ curned up, and then to lick colley’s leavings.’