In a moot, two pairs of students argue a fictitious legal case in front of a judge. To win, you do not necessarily have to win the legal case, but must make the best presentation of your legal arguments. But don't worry, we teach you how to do all that.

So that's mooting. But we also pursue certain broader aims. We try to help our members to secure employment by organising talks, networking events and a number of 'legal-themed' trips. We also organize a variety of socials and partner with other Law Societies for special events.

Please feel free to contact us through Twitter: @MootSoc , Facebook or Instagram: @uoamootsoc

- Foreword

-

University of Aberdeen Law Mooting Society - A Guide to Mooting

Foreword to the First Edition by The Rt. Hon. the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, The Lord Chancellor, London, August 1991.

I am delighted to have been asked, as Honorary President of the Law Mooting Society of the University of Aberdeen, to provide this foreword to the Society's first handbook.

When I first went to Parliament House as a pupil to a leading junior, now Lord Grieve, I had the opportunity of listening to great masters of the art of advocacy pleading in court. Like most of my contemporaries I spent a lot of my time listening to those distinguished advocates and seeking to assimilate the art of which they were such masters. My colleagues and I learned that there is no one right method of advocacy. Each of them had their own distinctive approach which suited their different personality but all were effective in their different ways. We learned that you had to know the facts and the law of the case you were pleading very thoroughly since the judges probed the case deeply as it was being developed. Generally it was useless to be tied to a speech carefully prepared in advance, since it was highly likely that the judge by careful questioning would throw a new light on the problem by which the argument might be advanced in a different way from that which had been envisaged in the study the night before. We learned that one had to be open to adopt and adapt suggestions that might be helpful while discarding with courtesy, but firmness, suggestions that might be put forward as obstacles.

Nothing that I have seen or heard in subsequent years leads me to believe that those very simple principles observed then are in any way flawed. They are, I think, as relevant today, both in court and moot, as they then were.

I very much hope that everyone who uses this handbook and participates in mooting will find it an enjoyable and educative experience.

I wish you all success.

- What is a Moot

-

A moot is a legal debate in a courtroom setting usually, but not exclusively involving a case taken on appeal. In a moot two teams of counsel attempt to persuade a judge of the strength of their case by reference to legal authority. In a student moot the teams consist of two pairs of students representing appellant and respondent debating in a moot problem.

A moot problem is a predrafted factual situation in which a point or points of law are in dispute. The task of each team is to support the side of the argument with which it has been presented. This is done with reference to legal authority such as case law, statutes, institutional writings and legal principles.

The role of the judge of the moot is to weigh up the arguments presented to him or her and to question counsel where this is necessary to allow the judge to understand or accept the points being made.

Counsel speak in the following order:

- Junior Counsel for the Appellant

- Junior Counsel for the Respondent

- Senior Counsel for the Appellant

- Senior Counsel for the Respondent

Counsel are required to present their arguments within a set time-limit, normally ten minutes for junior counsel, and fifteen minutes for senior counsel.

At the end of the moot the judge makes two decisions:

- Firstly, he gives his judgement on the law

- Secondly, he makes his decision as to the winning team in terms of mooting skills

- A Guide to Mooting

-

From here, you can access an electronic version of the Mooting Society's Guide to Mooting Handbook. Paper copies are available in the Heavy Demand section of the Taylor Library.

Authorship note: The First Edition of the Handbook was written by Alistair Carmichael and Michael Anderson in 1991, and the second by Michael Anderson with Euan Miller in 1993. The current web version is based on an earlier electronic version of the second edition, prepared by Vicki Stewart.

- The Skills Involved

-

Mooting is a combination of public speaking and debating, yet differs from both. The mooter does admittedly sometimes deliver a prepared speech, but only in so far as the judge is prepared to accept this. A speech which has become largely irrelevant due to the course of the moot will not recommend the deliverer's skills to the judge. The mooter must always be ready to be diverted from the line of argument which he envisaged delivering. For this reason straight delivery of a prepared text is not recommended and can even be perilous at times ...

The mooting is also something of a debater, in that he must be prepared to pick up points by his opponents and the judge, and those who are practised in the art of debating should be able to make the transition reasonably easily. However, the mooter is much more constrained by his subject matter than the debater, and must back up his arguments with legal authority rather than persuasive personal opinion. In addition, the mooter is denied the right to interrupt his opponents to question them directly, and cannot emply some of the more theatrical diversions which the debater can bring into play.

The best mooters are those who do three things well:

- They are prepared thoroughly, examining the problem closely and from all possible angles

- They produce solid, comprehensive (and comprehensible!) arguments as a result of their research

- They select their best two or three arguments, and present these clearly and calmly to the judge

The ability to do all these things while under pressure (and to remain calm whilst doing so) is one which is not to be under-estimated!

Put off by all this? Don't be!

These are skills which can be acquired with a little effort and experience, and once you have them you will find mooting to be a worthwhile and perhaps even rewarding pastime which will stand you in good stead in your future career, whether or not this is as a lawyer.

Remember everyone has to start somewhere. Perhaps the best starting point is to watch other students mooting before taking the plunge yourself. Feel free - moots are always open to spectators. The A.U. Law Mooting Society runs a smaller, less formal competition for first years later in the academic year, as do societies at other universities. Here you can, "cut your teeth" against others of similar experience and knowledge of the law.

To find out what real life "mooting" is all about it is a good idea to visit the Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary or your local Sheriff Court, where you will see qualified advocates and solicitors debating legal issues.

- Preparation

-

Once you have been presented with the moot problem the first thing to do is to read it - very, very carefully! The only facts on which you can rely in presenting your case are contained in the problem. NEVER try to introduce facts into the problem which aren't down there on paper. This is a surefire way of incurring the judge's wrath!

A couple of readings of the problem should make clear to you the issues to be debated in the moot. Once these have been identified it is time to start your research.

When researching your case, always bear in mind that you are a team. It will save precious time if you research different points of law independently. That said, however, it is absolutely essential that you and your partner should work together as a team, and that each should have a complete understanding of the points researched by the other.

First stop in your research will normally be a general source of law on the subject of the moot, such as Walker, Delict, McBryde, Contract, or Gordon, Criminal Law. The main use of these and like books is that they give a general statement of the law with appropriate authority such as case report citations or references to institutional writings.

It must be stressed, however, that these textbooks can become outdated and any authority taken from them should be checked to ensure its continuing validity.

Next base in your researches is to read the cases and other authorities. Consider all the cases on the subject and not simply those which suit your argument (if any!) It is never too early to start thinking how you might distinguish 'awkward' cases!

At all times during your research TAKE NOTES. These are useful in allowing you to build up a full picture of the law and undoubtedly save time later on.

- Choosing Authorities

-

By this stage you should have a fair idea of the arguments which you intend to employ in the moot and it is now time to select the cases, statutes and other authorities which you will cite to the court.

The number of authorities is usually limited to about seven or ten cases; but do not imagine that you must cite as many as are permitted. It pays to focus only on a few cases - this naturally disciplines your arguments and will enhance the clarity of your submissions.

NB When citing a case you should use the version in the most reputable case reports you can find, for example Session Cases rather than Scots Law Times, and the Law Reports (Appeal Cases, Family Division, Queens Bench and so on) rather than the All England Reports and the Weekly Law Reports.

It is permissible to use a casebook such as Gane and Stoddart where the case is otherwise unreported.

When citing a statute please bear in mind that it must apply in Scotland before you can usefully use it. Doing otherwise will be highly embarrassing and may cause offence!

When citing institutional writings you should beware of using an old edition. Always check with the clerk whether he or she has the same edition as you do - many institutional writings have been revised in the last 150 years.

As a general rule, modern day textbooks should not be cited to the court unless they contain an especially persuasive argument of law and you cite them at your own peril! If you feel compelled to cite textbooks, it is a good idea to stick to hardback tomes such as McBryde, Gordon, Walker and Clive. Whilst Woolman and Lake, Contract, Stewart, Delict, Macdonald, Succession, and Jones and Christie, Criminal Law provide excellent aids in passing exams, they lack sufficient depth and stature to normally be cited as authority.

Beware of citing items that are way off the beaten track. A good rule of thumb is to stick to Scots and perhaps English sources. While an article is the Greenland Law Review may be on your side it is likely to be regarded with distain by most judges! Similarly views and reports in non-legal journals should in the main be avoided. You should ensure that such sources are essential to your case or that better authority cannot be found before relying upon them.

Avoid the temptation to "pack" your list of authorities to cover all eventualities. This will only annoy the judge (who has to attempt to familiarise himself with all the authorities submitted) and will annoy the clerk of the court (who has to make all the authorities available). It is particularly bed form to cite a "red herring" case or article. Such items can generally be picked out by the opposition quickly (because they invariably are 100 pages long and totally irrelevant) and therefore provides you with no advantage. Moreover this is extremely "uncourtly" behaviour.

Once you have received you opponents' authorities read any that you have not come across in your own researches. If a case cited by your opponents appears to go against you then you will have to distinguish it in the course of the moot and make a point of doing so. Do not ignore it.

Distinguishing a case can be done in one of three main ways:

- By arguing that the case has been over-ruled by one of the cases cited by you

- By arguing that the case can be distinguished from the case at issue on the facts or the law decided

- By arguing that the case was wrongly decided in that it conflicted with settled law or legal principle. In this third case, it will be necessary to argue that as a consequence the court ought to over-rule the earlier case (provided your court has that power).

Distinguishing cases is a fine art which you will become more adept at with practice.

For further information see Wilson; Introductory Essays on Scots Law, "Dealing with Decisions", p78-86.

- At the Moot

-

It is usually best to arrive about fifteen minutes before the start of the moot so that you can get settled into the surroundings, arrange your papers and get comfortable. Like in a real court, punctuality is a must.

Please note that there is no pre-match entertainment (pipe bands are out!) and no half-time interval.

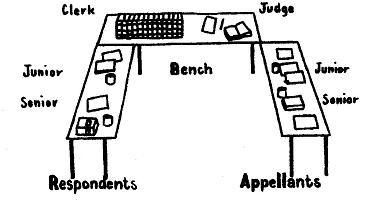

Sketch of the Courtroom at a Moot

The Court will be called to order by the Clerk shouting "Court" and counsel must rise at this point and remain standing until the judge is in place on the bench. A golden rule of mooting is that counsel must always stand when addressing the court.

Once the court has been called to order the judge will normally say "Who appears?"

This is the cue for senior counsel to identify him or herself and his or her junior counsel:

"Appearing for the Appellant My Lord is Mr John Prescott as Junior Counsel, and I, Mr Tony Blair as Senior Counsel."

The first introduction is made by senior counsel for the appellant. If he so desires he may introduce all four mooters.

Once counsel have been introduced the judge will invite junior counsel for the appellant to make his submissions to the court. What follows is a brief and by no means comprehensive outline of what is expected from each speaker (in order).

Junior Counsel for the Appellant

- Offers to provide a short précis of the facts of the case

- Outlines briefly the points of law on which the appellant's case is based, indicating which of these is to be dealt with by him or her, and which falls to be dealt with by his or her senior. (The judge will normally take a careful note of the outline which junior counsel presents, so it is advisable to deliver this part of your speech quite slowly, watching the judge's pen as you go.)

- Deals with the points of law mentioned to the judge

- Concludes

Junior Counsel for the Respondent

- Does much the same job in outlining the case in law for the respondent

- (There is obviously no need to provide another précis of the facts, but as the appellant's case has already been outlined then some mention should be made of the areas where you differ from your opponents)

- Responds to points made by his or her opposite number in so far as these have directly contradicted own submissions

- Deals with points of law mentioned to the judge (these should be adapted if the appellant has perhaps conceded a point you expected to argue. It is not advisable to plough on as if nothing had happened!)

- Concludes

Senior Counsel for the Appellant

- Starts by discussing and answering points raised by the respondents

- Outlines the points to be covered in his speech (there is not usually any point making any more than a passing reference to points dealt with by your own junior counsel.)

- Deals with the points mentioned to judge, which in the case of senior counsel ought to be the more difficult, complex and lengthy arguments. This is expected by the judge and is the reason why senior counsel has a greater time allocation

- Concludes with a summary of the entire arguments of the appellant counsel

Senior Counsel for the Respondent

- Responds to points made by the appellants

- Outlines own submissions and presents them

- (Senior counsel for the respondent has the advantage that the appellant's case has been fully developed before him. The corresponding disadvantage is that the case may have moved further from the area of law which counsel has researched and prepared. If this is the case you must take account of this and adapt to the changed circumstances. This may require a little speaking off the cuff, which is indeed very difficult, but if you can manage it, it will only do you good when the judge comes to consider the mooters' performances.)

- Concludes with a summary of the entire arguments for respondent counsel

- Court Address

-

Addressing the court is a valuable skill which it is worthwhile mastering in the moot arena because basically the same styles of address are used in real courts. Some of the points will need practice so that you get the right terminology every time, but the better mooter will look to do this to ensure a polished performance.

- Always address the court in the third person. The judge is always "my Lord." When addressing the judge, the word "you" is not used - it is instead "your Lordship."

For instance:

"My Lord, if I may now deal with the point Your Lordship raised earlier."

NB If the judge is female, ask before the start of the moot if she wishes to be addressed as "My Lady" and "Your Ladyship."

- Always be courteous and show respect for the judge. Speeches should start:

"If it pleases your Lordship" or "Thank you, My Lord."

NB Note however, the difference between obsequiousness and courtesy.

- Do not refer to your opponents by name, but as "My Learned Friend, Junior/Senior Counsel for the Appellant/Respondent." Your own partner may be referred to as "My Learned Senior/Junior".

- Do not give the court your opinions or beliefs on the law. Give the court your "submission". For example:

"I submit that the law is X...."

Do not say

"I think that that law is X...."

- Before finishing your speech it is generally best to invite the judge to ask any questions on the points you have raised.

Say:

"That, My Lord, concludes the arguments I wish to submit on behalf of the appellant/respondent. Perhaps there are some issues on which I may be of further assistance?"

If not, conclude:

"I am obliged, My Lord."

- Always address the court in the third person. The judge is always "my Lord." When addressing the judge, the word "you" is not used - it is instead "your Lordship."

- How to Cite Authority

-

As in addressing the court, there is an art to presenting authority to the court. When citing a case to the court you should not use written abbreviations. Instead quote the full form.

For example,

instead of saying

"Donoghue vee Stevenson 1932 S.C. (H.L.) 31..."

you should say

"Donoghue against Stevenson, reported in the 1932 volume of Session Cases at page 31 of the House of Lords reports".

Similarly, always refer to Her (or His!) Majesty's Advocate and not "H.M.A.".

When referring to a passage within a case, you should make it clear to the judge exactly where he will find the passage to which you wish to draw his attention.

For example, say

"Donoghue against Stevenson, reported in the 1932 volume of Session Cases at page 31 of the House of Lords reports, the speech of Lord Aitken on page 44, ten lines up from the bottom of the page, starting "Who then is my neighbour?"

Do not start to quote until you can see that the judge has found the exact place in the report. Always ensure that you and the court are using the same set of law reports. Don't cite from the Scots Law Times if you cited the Session Cases in you list of authorities!

It is often advisable to have a photocopy of the entirety of any case to which you intend to refer. Then, if the judge wants to draw your attention to a different passage in the report you will be able to understand his point and respond.

When citing a case, it is often advisable to offer to acquaint the judge with the facts of the case. This offer is often not taken up, but it is still polite to do so.

- Speaking Skills

-

One of the most important skills of the mooter is straightforward public speaking. You should remember that no matter how familiar you are with your arguments, the judge is hearing them for the first time. You should always pay special attention to ensuring everything you say is clear and well-structured. Getting someone to read over your submissions before you present them is a good idea.

When speaking in the moot itself all normal rules of public speaking apply. Your delivery should be clear and proceed at a reasonable pace. Learn not to mumble into your chest or to put your hand up to your mouth. These signs of nervousness will impair the clarity of your voice. Don't get carried away with body language either. You are presenting a case in law, not a comedy routine.

This rules out excessive use of humour. Telling the one about the Scotsman, the Englishman and the Irishman does not advance your case in law, (and wastes valuable time). As in all public speaking, good eye contact with the judge is important. This gives an air of confidence, suggesting that you are convinced by what you are saying and that the judge should be convinced too. Don't play to the audience - they are for your purposes totally irrelevant.

While it is obviously important to make yourself heard and to appear calm and confident, do not be too forceful in your delivery. The judge may respond to aggression with aggression, and this is clearly not in your favour. Few, if any judges will respond positively to a bullying or hectoring counsel. Your aim is to persuade the judge, not to intimidate him! A little humility goes a long way. That said of course, if you feel that the judge is wrong in his understanding of your case, then you must gently point this out. When the point the judge disagrees with is the central thread of your entire argument then you should be prepared to stand your ground and argue your case. The judge may force you to do this purely to see your mooting skills. If the argument is less important, perhaps one of a number of submissions, and it is quite clear that it is not acceptable to the judge, do not try the patience of the court and waste time by pursuing a hopeless cause - move on to your next line of argument.

Timing is a very important factor. First and foremost you must speak slowly enough to be understood, so you should tailor the length of your submissions to the point at which you are speaking at a reasonable pace and are still comfortably within your time limit. Many judges take copious notes during a moot - you should keep an eye on the judge's pen and slow down accordingly. Remember that you expect a lecturer to go slowly enough for you to take lecture notes - don't demand more from the judge than you would of yourself in that context.

It is not a wise idea to have your submissions up to the full time limit. Remember that in the moot itself you will have to take account of the time the clerk takes to find the authorities, the judge's questioning and so on.

Perhaps you should practice your submissions out loud to your friends. The more familiar you are with standing up in front of an audience and making your submissions, the more fluent, confident and persuasive you will appear. You can also time yourself this way.

Finally, remember the advice of the Sheriff who said:

"Reserve high drama, histrionics, emotions, tears and blood for a jury. Judges are immune".

- Answering Questions

-

Answering questions well can make the difference between winning and losing a moot. The best advice is simply to prepare well. The more you prepare, the better a grasp of the law and the facts you will have, making your answering of questions easier.

It is a good idea to try and spot the weaker parts of your argument in advance as this is where most tricky questions arise. Watch out for what seem to be trick questions. Many questions may seem easy to you - they probably are. Many judges do ask easy questions simply to check that you know the basics.

If the judge asks a question to which you do not immediately know the answer DO NOT PANIC. Don't be afraid to stop for a few seconds to think about it. If necessary, ask permission of the judge to consult with your partner.

Another tactic is for junior counsel to leave a question to be dealt with by his or her senior. If this is done then senior counsel must make a point of doing so.

- Note for Guidance of the Moot Clerk

-

The clerk's job is to be chief administrator at the moot. Although a moot will normally be presented to the "court" by a third person, in all other respects the clerk takes responsibility.

The clerk has two main tasks. Firstly, he or she is responsible for the collection of authorities and their transfer to the moot venue, and secondly, he or she must assist the judge on the night.

The clerk will receive the two lists of authorities on the day before the contest. He or she should check which authorities are common to both lists, and whether the citations are also common! On the day of the moot the clerk is responsible for gathering all the authorities from the law library and notifying the librarians. The clerk is advised to mark the place in the volume of the case cited to same time at the moot.

On the night the clerk must call the court to order and lead in the judge. During the debate the clerk must listen keenly to the argument, and when a case is cited, must find the volume and the place, and pass the open text to the judge. Although there is a strong temptation to get caught up in the arguments (or to fall asleep!) the clerk must stay alert.

Despite all this, the job of clerk is a relatively simple one, and is a good way to get involved and watch mooters in action close up.